|

The

UN's

involvement in the Western Sahara issue started

on December 16, 1965, when the General Assembly

adopted its first resolution on what was then

called Spanish Sahara, requesting Spain to "take

all necessary measures" to decolonize the

territory, while entering into negotiations on

"problems relating to sovereignty".

Between 1966 and

1973 the UN General Assembly adopted seven more

resolutions on the territory, all of which

reiterated the need to hold a referendum on

self-determination. Thus, the UN stated in

unambiguous terms from the start that the

Western Sahara conflict could be resolved only

through an act of self-determination, in keeping

with the Declaration on the Granting of

Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples.

This position has been maintained by the

organization up to the present day. |

|

BIPPI

|

||||

|

Dispute for control of Western

Sahara

–

1975/1991

(to present day)

NOTE: Translated from Arab,

names can be written in many ways, according to

English, French or Spanish pronunciation. It is not always

clear which the current English version of them is.

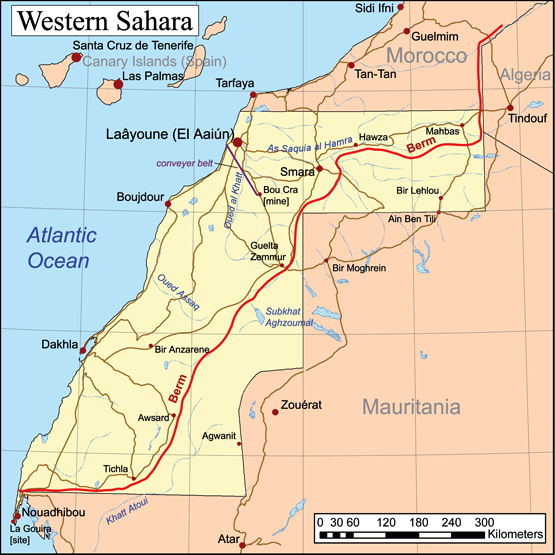

Western Sahara

(Sahara Occidental in Spanish) is a territory

of north-western Africa, bordered by Morocco to the

north, Algeria in the northeast, Mauritania to the

east and south, and the Atlantic Ocean on the west.

It is one of the most sparsely populated territories

in the world, mainly consisting of desert flatlands.

The largest city is Laâyoune (El

Aaiún), which is home to over half

of the population of the territory.

Western Sahara is mostly administrated by

Morocco as its

Southern Provinces. The

Polisario Front claims to control the area behind the

border

Moroccan wall (the red line in the map) as the

Free Zone on behalf of the

Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic.

The Polisario has its home

base in the

Tindouf refugee camps in

Algeria.

Read more on

Western

Sahara. The Kingdom of

Morocco and the

Polisario Front independence movement (and

government of the

Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic or SADR)

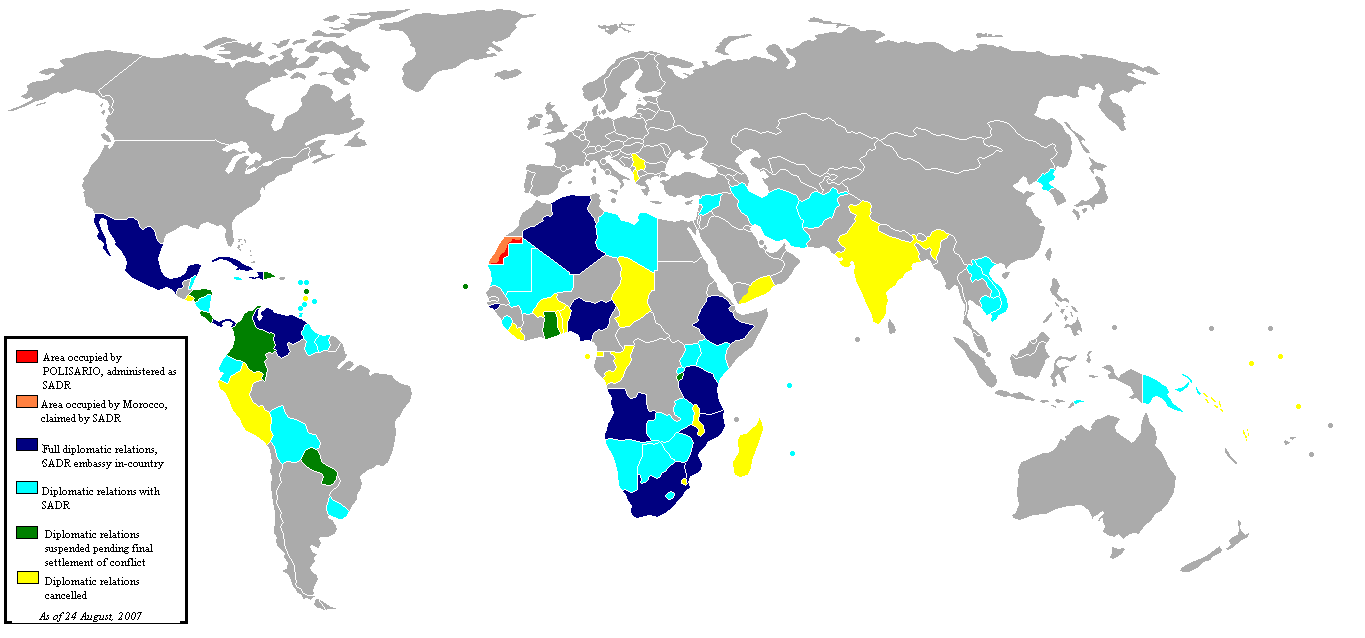

dispute control of the territory. Since a

United Nations-sponsored cease-fire agreement in

1991, most of the territory has been controlled by

Morocco, with the remainder under the control of

Polisario/SADR. Internationally, the major powers

such as the United States have taken a generally

ambiguous and neutral position on each side's

claims, and have pressed both parties to agree on a

peaceful resolution. Both Morocco and Polisario have

sought to boost their claims by accumulating formal

recognition, from largely minor states. Polisario

has won formal recognition for SADR from roughly

45 states, and was extended membership in the

African Union, while Morocco has won formal

recognition for its position from 25 states, as well

as the membership of the

Arab League. In both instances, recognitions

have over the past two decades been extended and

withdrawn according to changing international

trends.

Western Sahara has been on the

United Nations list of Non-Self-Governing

Territories since the 1960s when it was a

Spanish colony. It is considered today the last

case of incomplete

decolonization.

ECHO dossier on Western Sahara.

TYPE OF CONFLICT

The dispute is today between:

<Saharawi is the most commonly

used term for the natives of the Morocco-occupied Western Sahara.

Ethnic Saharawis are however found in southern Morocco and northern

Mauritania as well, the Western Sahara conflict having fractured

this tiny nomad people into several communities forced to exist

under wildly differing cultural and political conditions. The exact

size of the Saharawi ethnic group is unknown, and due to the

political dispute it is hard to find neutral accounts, but it is

probably somewhere over 500.000. Of which 200-250.000 are original

inhabitants of Western Sahara.

<Moroccans are Sunni Muslims of

Arab, Berber, or mixed Arab-Berber stock. The Arabs invaded Morocco

in the 7th and 11th centuries and established their culture there.

Morocco's Jewish minority has decreased significantly and numbers

about 7.000. Most of the 100.000 foreign residents are French or

Spanish; many are teachers or technicians.

CASUALTIES

Polisario received support by Algeria

and Libya (till 1984). Its troops are estimated 2,000 to 12,000 in the

so-called

Free Zone, but they were much more in the past years.

Over the centuries there have been historical links

between Morocco and Western Sahara. These connections were not in

the modern sense of a state or political rather more through

religious, cultural and personal contacts. The presence of the

trans-Saharan trade routes meant that the region was a place where

different cultures and peoples met as they passed through, each

leaving their mark. Then, as the history of the Saharawis and Moroccans is strongly mixed with that of all the

neighbouring countries, what really makes today a "people" out of

them, like for other African and no-African countries, is not the

reference to borders of the pre-colonial past but the will of people

who identify themselves in the same social, religious and linguistic

print.

The earliest recorded

inhabitants of the Western Sahara in historical

times were agriculturalists called Bafour. The

Bafour were later replaced or absorbed by

Berber-language speaking populations which

eventually merged in turn with migrating Arab

tribes, although the Arabic speaking majority in the

Western Sahara clearly by the historical record

descend from Berber tribes that adopted Arabic over

time. There may also have been some

Phoenician contacts in antiquity, but such

contacts left few if any long-term traces.

The arrival of

Islam in the 8th century played a major role in

the development of relationships between the Saharan

regions that later became the modern territories of

Morocco, Western Sahara, Mauritania and Algeria, and

neighbouring regions. Trade developed further and

the region became a passage of caravans especially

between

Marrakech and

Tombouctou in

Mali. In the Middle Ages, the

Almohad and

Almoravid dynasties both

originated from the Saharan regions and were able to

control the area.

After

the fall of the Almoravid empire in

1147 the new Moroccan empires (Almohad,

Merinid and

Wattasid) retained sovereignty

over the western part of the Sahara

but the effectiveness of it depended

largely on the sultan that ruled.

Towards the late

Middle Ages, the

Beni Hassan

Arab bedouin tribes invaded the Maghreb,

reaching the northern border-area of the Sahara in

the 14th and 15th century. Over roughly five

centuries, through a complex process of

acculturation and mixing seen elsewhere in the

Maghreb and North Africa, the indigenous Berber

tribes adopted

Hassaniya Arabic and a mixed Arab-Berber nomadic

culture. With

the coming to power of the

Saadi Dynasty the sovereignty of

Morocco over the western part of the

Sahara became formally complete

again: the Portuguese colonisers

were expelled from Cape Bojador and

from Cap Blanc and the borders of

Morocco were moved up to the Senegal

River in the south-west and to the

Niger River in the south-east (see:

Battle of Tondibi in 1591). The

situation did not change with the

coming of the (present)

Alaouite Dynasty in 1659.

In

the second half of the 19th century

several European powers tried to get

a foothold in Africa. France

occupied Tunisia and Great Britain

Ottoman Egypt. Italy took possession

of parts of Eritrea, Belgium invaded

Congo while Germany declared Togo,

Cameroon and South West Africa to be

under its protection. It was the

so-called

Scramble for Africa, the very

start of a new wave of colonialism.

After the agreement among the European colonial powers at

the

Berlin Conference (1884 - 1885) on the division of spheres of

influence in Africa, Spain seized control of the Western Sahara and

declared it to be a Spanish protectorate in a series of wars against

the local tribes. In the meanwhile a re-organization of the Saharawi indipendentist forces brought to the foundation of "Harakat Tahrir Saguia El Hamra wa Uad Ed-Dahab" or simply "Movement for the Liberation of the Sahara" (MLS), whose first actions did not have military character and took the shape of civil resistance.

In June

17, 1970, the colonial government called for a Saharawi

manifestation in Laâyoune in order to express the adhesion to the Mother Native

land (Spain).

UN

resolutions passed in 1972 (n. 2983) and 1973 (n.

3162), affirming the right of Saharawis to self determination and

independence.

On May 10, 1973, the Constitutive Congress for the Frente Polisario, was

held. The

Polisario (Frente POpular para la LIberacion de

SAguia el Hamra y RIO de Oro) was born as a political

movement, coming from the meeting of survivors of the MLS with a

group of Saharawi students in Morocco.

By 1974, the Spanish regime was in serious difficulties at

home and feared

the consequences of a military confrontation with Morocco, while the General Franco was

old of 82 years and near to death. The

Spanish population was not laid out to accept a war, and if a

conflict burst, Spain would have been exposed to the diplomatic and

economic reprisals of the Arab world. "I. Was Western Sahara (Saguia El-Hamra y Rio de Oro) at the time of colonization by Spain a territory belonging to no one (terra nullius)?" "II. What were the legal ties between this territory and the Kingdom of Morocco and the Mauritanian entity?" On January 16, 1975, Spain officially announced the suspension of the referendum plan, pending the opinion of the court. 65% of Bou-Craa exploitation was sold to Morocco. In May-June an important mission of enquiry was sent by the UN secretary-general to Western Sahara, Spain, Morocco, Mauritania and Algeria. After many days of travelling the members of the mission could affirm in an unambiguous way that "there was an overwhelming consensus among Saharans within the Territory in favour of independence and opposing integration with any neighbouring country...." On October 16, 1975 the IJC emitted its clear advisory opinion: on one side the Western Sahara was not a 'no man's land' before the Spanish occupation, there was evidence of a tie of allegiance between some, though not all, of the tribal chiefs and the Kingdom of Morocco and the Mauritanian entity. "Thus the Court has not found legal ties of such a nature as might affect the application of General Assembly resolution 1514 (XV) in the decolonization of Western Sahara and, in particular, of the principle of self-determination through the free and genuine expression of the will of the peoples of the Territory." Hours later the delivering of the advisory opinion, King Hassan II claimed the opposite. The IJC, he told his subjects, had vindicated his irredentism. Then he announced the Green March, and, on November 5, 1975, he ordered 350.000 unarmed Moroccans, Koran in hand, protected by the army, to march into the north of Western Sahara to reassert the sovereignty of the Territory. On November 6, the UN Security Council "deplored" this action and ordered Hassan to withdraw the marchers.

On

November 14, 1975, Spain, Morocco and Mauritania signed the

tripartite

Madrid Agreement

by which Morocco acquired the northern two-thirds of the territory,

while Mauritania acquired the southern third. Tens of thousands of people fled to Algeria, in the region of Tindouf, to escape the violence of the fighting. On February 18, 1976, the columns of refugees were victims of bombardments with napalm, phosphorus and cluster bombs by Moroccan aviation. Many were reported dead near Guelta Zemmour and Bir Lahlou.

Spain officially ended its

administration in Western Sahara on

February 26, 1976, as the UN

received communication of the end of

the Spanish presence in the

territory and Spain's last soldier

departed the territory. Spanish

Foreign Minister, Areilza, affirmed

that Spain did not transfer to

Morocco and Mauritania the

sovereignty over the territory but

only transferred its administration.

On

February 27, 1976, the Polisario proclaimed the independence of Western Sahara and the birth of the

Saharawi Arabic Democratic Republic

or SADR.

In May,

being completed the evacuation of the refugees, the Polisario

began offensive military actions.

In June a column of Polisario guerrillas crossed 1,500 km of desert and shelled Nouakchott, the Mauritanian capital.

In

February 1977 Spain and Morocco signed a fishing agreement;

consequently Polisario began attacking on Spanish fishing vessels.

Polisario

guerrillas severely weakened Mauritania by repeatedly cutting the

Zouerate-Nouadhibou railway line that was the main route for the

export of iron ore, on which Mauritania depended for 80-90% of its

export earnings. Impoverished Mauritania couldn't afford the costs

of the war. In July Nouakchott was attacked again by the Frente Polisario, and President Daddah was forced to appoint a military officer to head the ministry of defence. 9.000 Moroccan troops were airlifted into Zouerate to reinforce Mauritanians, so that the Mauritanian military (15.000 to 17.000 troops) resented its role as a back-up force to the Moroccans.

In

October 1977, after two more French citizens were seized during a raid on

the railway, French President Giscard d'Estaing ordered the military action called

Opération Lamantin.

On July 10, 1978, in Mauritania, President Ould Daddah was deposed in a coup led by army officers who pledge to restore peace. Then, Polisario declared a cease-fire in Mauritanian territory and in one year the two belligerants signed the Algiers Agreement, by which Mauritania renounced its claim to Western Sahara and promised to withdraw completely within seven months. The Polisario, in return, renounced all claims regarding Mauritania.

In summer

1979, Polisario guerrillas overrun the Moroccan base of Lebouirate,

where they took 111 prisoners and destroyed 37 tanks T-54. Polisario hold the town for over a

year. They fought their way into Smara and captured another Moroccan

base at Mahbes. On Novembre 11, 1980, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution (A/RES/35/19) urging Morocco to "terminate the occupation of the Territory of Western Sahara".

At the

beginning of the '80s, after Polisario's army (ELPS) defeated several times the

Moroccan FAR, France sent military advisers to King Hassan II. Followed

American advisers in 1982 and Israeli advisers in 1985. The construction of the berm resulted in what amounts to a military stalemate, so that military activity was scaled down in the mid-1980s. Polisario had control of a big chunk of the country, but anything of any importance (the fishing ports, the cities and the phosphate mines) is on the Moroccan side of the wall.

On

February 22, 1982, the OAU admitted the SADR as the 51st

full-fledged member. As a consequence, by time, 73 states recognised

the SADR while Morocco left the Organisation. On August 11th, 1988, UN Secretary-General Pérez de Cuéllar proposed a cease-fire and the organisation of a referendum under international control, on the base of the 1974 Spanish census. On 30 August 1988, Morocco and Polisario accepted the UN-OUA baked peace plan and in November Polisario decreed a unilateral cease-fire. A UN resolution approved the peace process, but when Spain voted in favour of the resolution, for reaction King Hassan II cancelled its visit to the Iberian country and, at the same time, the rivendications on the official press on Ceuta and Melilla, the remaining plazas de soberanía ("places of sovereignty"), became stronger.In March 1989, the European Parliament pronounced for the self-determination referendum and several times expressed concern about the violation of human rights in the occupied territories. In 1990, the UN Security Council approved the resolution 658/90 containing the "Settlement Plan" for Western Sahara. By the resolution 690/91 the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) was established in accordance with the Settlement Plan.MINURSO was created as an integrated group of United Nations civilian, military and civilian police personnel; up to total 1.000 civilian and 1.700 military personnel, it was mandated to:

A long process of

identification began, towards the referendum on the

self-determination of the Saharawis which should be made in

January 1992.

THE DISPUTE FROM 1991 TO PRESENT DAY

In October/November 1991, in clear violation of the cease-fire norms, Morocco sent thousands of settlers to the occupied territory and attempted to block the referendum process by forcing the UN to accept them as voters. The technical materials of the UN were blocked in the Moroccan ports and the UN flag could not wave on Laâyoune, capital of the occupied Western Sahara. In his report to the Security Council S/22464 of 19 December 1991, just before finishing his mandate, UN Secretary-General Pérez de Cuéllar accepted Moroccan positions, essentially asking for a revision of the electoral body opening the right to vote to pro-Morocco settlers. The Secretary-General regretted that slow progress in the accomplishment of certain tasks had made it necessary to adjust the timetable of the settlement plan, largely due to the complexity of the identification process, aimed at establishing the list of those who would vote in the referendum, and the parties’ different interpretations of the plan in that regard." (UN repertoire) The largest most permanent social unit was the Tribe that, in that part of the world, is also known as Kabil. The Tribes break down into Fractions and the latter into Sub-fractions. Fractions and Sub-fractions go back six to eight generations. The smallest meaningful social structure is the Ahel, or family unit, that gathers the last three to four generations. The Head of the Tribe or Tribal Fraction is the Sheik. Every tribe has its own laws and deliberative bodies (the Assembly of Notables or Djema'a). The tribes are the sole structures at which the claim of sovereignty could be laid. Openly protesting against this new position, Secretary-General's Special Representative for the Western Sahara, the Swiss Johannes Manz, resigned. For the first time a Secretary-General report was not immediately accepted by the Security Council. Only at the end of the year the Security Council approved the new position of the Secretary-General and dismissed him; the new Secretary-General, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, was given mandate to present a new report before February 1992. Before December 1991, the 3 accepted criteria to be registered as qualified voter for the referendum were:

In his 19 December 1991 report, just few days before the end of his mandate, Pérez de Cuéllar accepted 2 more criteria:

In January 1992 the referendum was delayed "sine die" following disputes about who is eligible. The UN collapsed under the debts, MINURSO was impotent while Moroccan authorities repressed independentist demonstrations and moved new farmers to the occupied territories. A mission of the US Senate in the Western Sahara, published on February 5th, affirmed: "The responsibilities of the serious delays of the peace plan are to be given to Morocco, to its wish not to collaborate and to the missed support of the UN Secretary-General to the MINURSO". Boutros-Ghali proposed a delay of at least three months to save the UN-baked plan. The Pakistani Sahabzade Yaqub Khan, generally considered pro-Morocco, was named as new Special Representative for the Western Sahara.

On May 29, 1992, in the report S/24040, Boutros-Ghali indicated the greatest

obstacle for the realization of the referendum in the criteria of

identification of the eligibles to the vote. In answer the UN

Security Council invited the parts in conflict to "exceptional

efforts to assure the success of the plan of peace." On September 4, 1992, in Morocco was held a referendum for the approval of the new Moroccan Constitution, extended to the Western Sahara, with which the King Hassan II kept on reserving himself interior, foreign and religious politics. Followed the Moroccan town elections, extended to the Sahara. The civil Saharawi population of the occupied territories started to manifest against the Moroccan presence. The intervention of the Moroccan special forces was hard and hundreds of Saharawis disappeared following the repression. On January 28, 1993, UN Secretary-General Boutros-Ghali delivered the report S/25170, where three possibilities were proposed to improve the peace plan: 1) to intensify the dialogue among the parts so that to arrive to an accord on the way to organize the referendum; 2) to celebrate the referendum the first possible substantially modifying the electoral body; 3) to abandon the actual plan of peace and look for an alternative solution. On March 2, 1993, the resolution 809 of the UN Security Council welcomed the first proposal contained in the relationship of the Secretary-General, it confirmed the preceding resolutions and expressed strong worry for the persistent divergences among the two parts. Confirming that the 1974 Spanish census is the base to establish the eligibles to the vote it didn't admit the criteria of amplification pretended from Morocco; the Special Representative was entrusted of to swiftly proceed to the application of the resolutions. In those months, reports from US Department of State, the European Parliament and Amnesty International expressed worry for the lack of respect of human rights in Morocco. On May 31st, 1993, Boutros-Ghali visited the region. Followed legislative elections in Morocco, extended also to the occupied Western Sahara. On July 16, 1993, there was a meeting in Laâyoune among delegations of Frente Polisario and Morocco, publicized by Rabat as a meeting between monarchy-faithful Saharawis and dissident Saharawi, with no discussion about the Moroccanity of the Sahara. In the report S/26185, Boutros-Ghali expressed satisfaction for the meeting of Laâyoune, also admitting fundamental divergences among Polisario and Morocco. On October 25th, a following meeting in New York among the Polisario and Morocco failed. Rabat, at the last moment, changed the composition of the delegation inserting dissidents from the Polisario and excluding representatives of its own government. For Morocco the problem of the Western Sahara existed only for the Saharawis that had to find, among them, a pacific solution in the frame of the Moroccan community. This attitude was harshly criticized by the members of the UN Security Council; particularly the representative of the United States defined the behaviour of Morocco "provocative and unacceptable" affirming that "the patience of USA is at the limit." On March 10, 1994, Boutros-Ghali delivered the report S/1994/283 (not available in the UN database but quoted in successive reports), making the point on the work of the Committee of Identification and proposing three options to go out of difficulties: to) to organize the referendum at the end of 1994 without the collaboration of one of the two parts and following the attached calendar;

b) to

continue the job of the Committee of identification on the base of

the criteria established by the Secretary-General and to try, in the

meantime, to get the cooperation of the two parts,

with the intention to hold the referendum c) to progressively put an end to the operation of the MINURSO, to suspend the process of identification and to maintain a shortened military presence in the territory only to preserve the cease-fire. The Resolution 907 of the UN Security Council opted for the solution b) asking the Identification Commission to complete the analysis of all applications received and proceed with the identification and registration of potential voters by 30 June 1994, with a view to holding the referendum by the end of 1994.

On July

12, 1994, Boutros-Ghali delivered the

report S/1994/819 according

to which around 76.000 potential electors were enrolled in the

lists. The identification of these electors was not begun for the

difficulties risen with the designation of the observatories of the

OAU, undesirable to Morocco.

On May 26, 1995,

the political stalemate brought the UN Security Council to approve

the resolution 995 (1995) and send a mission to Western Sahara, from

3 to 9 June.

The terms of reference of the mission, as set out by the Security

Council (S/1995/431), were as follows: In May 1996, as the situation (lack of transparency, trust and goodwill) didn’t change, the UN suspended the identification process blaming both sides for problems and recalled most MINURSO civilian staff. Military personnel stayed to oversee the cease-fire.

In 1997,

after years

of stalemate, the deadlock was broken thanks to the

appointments taken by the new UN Secretary-General

Kofi Annan and

his new envoy to Western Sahara,

James Baker III, former US Secretary of

State.

After the arrival

of

Mohammed VI of Morocco to the throne, in July 1999,

Morocco had reneged on its 1991 and 1997 agreements on a vote on

independence. Polisario argued that Morocco had thus broken a main

condition of the 1991 cease-fire agreement, which had wholly hinged

on the independence referendum.

In 2000, negotiations between Polisario and Morocco failed in

London and Berlin. Agreements were reached only on the release of

Prisoners Of War (POWs,

1,800 Moroccans according to

ICRC 1998 report),

a code of conduct for a

referendum campaign and

UN authority during a transition period. Further talks in Geneva broke down.

In the words of Kofi Annan (S/2002/178,

paragraph 30), "neither party had shown any disposition (...) to

discuss any possible political solution in which each could get

some, but not all, of what it wanted and would

allow the other side to do the same". In May 2001, Morocco presented to the United Nations a new proposal, commonly known as "third option " on Western Sahara; the Moroccan project provided a «substantial devolution of authority» to local people with final status to be determined by a referendum five years later. Polisario agreed to enter autonomy as a third option on the referendum ballot, but refused to discuss any referendum that did not allow for the possibility of independence, arguing that such a referendum could not constitute self-determination in the legal sense of the term.On June 20th, 2001, UN Secretary General Kofi Annan presented his report S/2001/613. He proposed UN to abandon the 1991 settlement plan by offering instead a "framework agreement" following the "Baker I" plan. UN Security Council approved a resolution extending the mandate of the UN Mission in Western Sahara by five months, until the end of November 2001. In July 2001 the OAU ministerial session firmly rejected a request from the Senegalese foreign affairs minister backed by his counterparts from Gambia, Gabon, Burkina Faso, to register on the agenda of the OAU summit of Lusaka the question of Morocco admission to the African Union.

At the

end of August 2001, James Baker III, met in Wyoming with representatives of

the Polisario and the Governments of Algeria and Mauritania

in Pinedale, Wyoming. Baker considered that the only way to put an

end to the stalemate was through a negotiated solution based on an

autonomy within the framework of Moroccan sovereignty. Baker

proposed to drop the referendum for the time being and let Morocco

guaranteed sovereignty over the territory for four years, including

Moroccan control of internal security and the judicial system. In

exchange, the Saharawis were offered some

leeway in controlling their own economic and social affairs,

some regional autonomy prior to moving towards an unspecified

political settlement at some point in the future.

In 2001 Morocco divided offshore oil exploration rights on the Western Saharan coast between a US and a French oil company. On December 2, French President Jacques Chirac of France described the Western Sahara as Morocco's Southern Provinces. If in the 1990s the Moroccans paid lip service to international law and the principle of self-determination, in this moment they overtly scorned it, buoyed by the knowledge that France will always back them to the hilt and the US are unlikely to alienate one of their few close Muslim allies. Tension mounted in the region as the referendum had been delayed 12 times. On January 2, 2002,

the Polisario released 115 of the 1,477 Moroccan POWs hold in Tindouf.

They were repatriated under the auspices of the International Committee of Red

Cross. Despite the political stalemate, both sides showed the only

willingness to implement the UN-baked Settlement plan.

I n 2002 the UN Legal Department declared Western Sahara as a Non Self-Governing country awaiting decolonisation. Neither UN nor OAU considered Morocco the legal administering power in the territory.The president of the Spanish Government, Jose Maria Aznar, affirmed that there are no reasons to change Spain's traditional position on Western Sahara, that maintains its support to the effective implementation of the UN settlement plan, which calls for a self-determination referendum. So the Moroccan army briefly occupied the small and uninhabited Isla Perejil, but left without fighting shortly afterwards, when Spain sent in soldiers. In May SADR and the Democratic Republic of East Timor established diplomatic relations. On May 27th, 2002, the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) announced that it has signed a Technical Cooperation Agreement (TCA) with the British-Australian exploration company, Fusion Oil & Gas plc, that will lead to a detailed assessment of the oil and gas potential of the offshore territorial waters of the state. So, oil exploration were being conducted in earnest both on and offshore, with rival transnational companies seeking rights from Morocco (Kerr-McGee) and Western Sahara (Fusion and Premier). In July 2002 the Security Council voted to extend the mandate of MINURSO. On November 6th, 2002, in his first public dismissal of the UN Settlement Plan for Western Sahara, Morocco's King said it is "obsolete" and "inapplicable". Speaking on the 27th anniversary of the green march, supported by France, Mohamed VI said the territory could be granted autonomy but should be part of Morocco. In January 2003, the second version of the Peace Plan for Self-Determination of the People of Western Sahara (Baker II) was delivered. The UN Security Council accepted the plan in July 2003 (Resolution 1495), supporting it "as an optimum political solution" and extended the mandate of MINURSO till October 2003.The plan aimed at instituting a semi-autonomous Saharan self-rule by a "Western Sahara Authority" for a period of five years, after which the referendum had to be held, with all the population of Western Sahara allowed to vote, included the 200.000 or so Moroccan settlers who have been enticed to the territory by subsidies and relocation deals. In a surprise move, the Polisario accepted the document as a basis of negotiations; Morocco stalled for several months, but eventually rejected the plan, stating that the kingdom will no longer accept independence as one of the ballot options. In the same Resolution 1495 (comma 4) the UN called upon the Polisario to release without further delay all remaining POWs in compliance with international humanitarian law. In January 2004 MINURSO's mandate was extended until April and then for another year. But the peace process was deadlocked, so that the envoy James Baker III, frustrated over the lack of progress in reaching a complete settlement acceptable to both the parties, resigned from his position in June 2004, Peruvian Alvaro de Soto took his place.

On March 13, 2004, the leaders of eleven political parties

expressed unanimously "their dismissal of all manoeuvres of the enemies of the territorial unity that persists in

their vain attempts aiming to undermine the territorial integrity of

the Kingdom" The SADR Government could never operate from Laâyoune, but from a small patch of desert over the border in Algeria where over 160.000 Sahrawi refugees, who have lived in refugee exile for almost three decades, always dependent on UN food aid, named their own ‘temporary’ settlements after the major cities of their homeland: Laâyoune, Smara, Aoserd and Dakhla. The real Laâyoune, once the capital of Spanish Sahara, remained a dusty, modest place with no notable architectural features, despite significant investment by the occupying Moroccans over the past 30 years. At that time 404 Moroccan POWs were still held by the Polisario. Some had been in captivity for more than 20 years. In the meanwhile something like 70,000 Saharawis were living in the Territory under Moroccan rule. On April 29th, 2005, the UN Security Council voted unanimously to extend the mandate of MINURSO through October 31. Personnel comprised then ca. 500 people, including local staff. At the same time Reporters sans frontiéres denounced the impossibility for journalists to make reports about Western Sahara, because of Moroccan repression.

At this

point, prospects for the Saharawis looked bleak. But in September

2004 South Africa announced that it was

formally recognizing the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic, affirming

that its decision was in line with "the principles and objectives

enshrined in the African Union and United Nations Charters".

President of South Africa Thabo Mbeki’s letter to the UN explaining

the decision made it clear he believed Morocco was no longer to be

trusted on this issue.

Since early

2005, the UN Secretary General stopped referring to the Baker Plan

in his reports, considering it largely dead. No replacement

plan was made, which could result in renewed fighting. In July 2005, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan appointed Peter van Walsum of the Netherlands as his Personal Envoy for Western Sahara. On August 17, 2005, Polisario announced the release of all all remaining 404 Moroccan POWs, who were repatriated to Morocco by the International Committee of the Red Cross.

In June 2005, Kenya

gave full recognition to the SADR, followed by Uruguay in December.

On the other side, the same month,

Sudan started to openly support

Moroccan sovereignty over the Western Sahara.

UN Security Council Resolution 1634 (2005) followed the report of the UN Secretary-General of 13 October 2005 (S/2005/648). It only reaffirmed the UN "commitment to assist the parties to achieve a just, lasting and mutually acceptable political solution, which will provide for the self-determination of the people of Western Sahara."

Kofi Annan said in his report

S/2005/648: From October 2005 to February 2006 Peter van Walsum consulted Polisario Algeria, Morocco and other countries. On April 19, 2006, the report S/2006/249 was delivered, containing no steps onward.

From the

report S/2006/249: On March 25, 2006, in the founding speech of the Royal Advisory Council for Saharan Affairs (CORCAS), King Mohammed VI clearly affirmed the impossibility to go on with UN peace plan; instead he proposed autonomy for Morocco's Southern Provinces (Western Sahara), pointing out that Morocco will never give up even not a grain of sand of its territory. On 26 July, 2006, the European Union signed a fisheries agreement with the Government of Morocco whereby fishing vessels from countries in the Union would gain access to the territorial waters off Morocco. On

29 July 2006, seventh anniversary of his accession

to the throne, King Mohammed VI of Morocco gave a

speech in which he proposed a plan for the

autonomy of Western Sahara giving to CORCAS the

charge to submit a plan. Then he made visits

to a number of countries to explain the proposal.

STATUS OF THE DISPUTE AT PRESENT

DAY

As in the

UN Secretary-General's

Report S/2007/202

of April 13, 2007, both Morocco and Polisario presented

officially separated

proposals.

Moroccan initiative received the backing of the USA

and France. In a letter to president Bush, 173

members of US congress endorsed the plan. On

June 18-19, 2007, discussions

started at

Manhasset, New York, between the

Moroccan government and the representatives of

the Polisario, involving the neighbouring

countries,

Algeria and

Mauritania.

The parties held separate meetings with

Peter van Walsum,

as well as two sessions of face-to-face discussions,

for the first time since direct talks had been held

in London and Berlin in 2000. On December 14-16, 2007, the 12th Congress of SADR was held in the isolated Polisario-controlled outpost of Tifariti. More than 1,500 delegates discussed if resuming armed struggle, pursuing negotiations or starting preparations for the resumption of war while pursuing negotiations at the same time. Moroccan government officials addressed the gathering at Tifariti as illegal, urging the UN to prevent it from taking place. Polisario's general secretary, Mohamed Abdelaziz, stated at the congress that he does not want a military solution. However, he warned that if Polisario were to be forced to resume the armed struggle, it would bring with it a fierce war of incalculable consequences for the stability of the entire region. As international delegates and the media left the congress after two days, intense discussions among the Polisario representatives prolonged the congress an additional 48 hours. According to Polisario spokesperson Mhamed Khadad, the result was a decision to meet again in six months, when a final decision on taking arms will be determined. On January 7-9, 2008, a third round of peace talks (Manhasset III) was held in Manhasset, just outside New York City. UN mediator Peter van Valsum said the parties continued to be far apart on the question of independence. Morocco maintained that its sovereignty over Western Sahara should be recognized and affirmed that independence cannot work as ethnic Sahrawis live in four different countries and a referendum is impossible to stage. The Polisario's position was that the Territory's final status should be decided in a referendum including independence as an option.

HUMAN

RIGHTS (from UN Secretary-General's

Report S/2007/202

of April 13, 2007 - paragraphs 39/40) The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has continued to follow the human rights situation in Western Sahara and the Tindouf camps and remains committed to ensure that the rights of the people of Western Sahara are fully protected. OHCHR continued to receive information alleging that human rights defenders’ trials were falling short of international fair trial standards. Allegations received from several sources also related to incidents where the rights to freedom of expression, association and assembly appear to have been compromised.

ASSISTANCE TO WESTERN SAHARA

REFUGEES

(from UN Secretary-General's

Report S/2007/202

of April 13, 2007 - paragraphs 29/32) With funding from the European Commission, the primary school infrastructure that was heavily damaged by the floods in February 2006 was reconstructed under the auspices of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The water distribution system, hitherto supplied by tankers in most camps, is being gradually replaced by more efficient and safe, piped water systems. Hygiene will thereby be improved and the risk of infectious diseases reduced. During the reporting period, a second stage of the safer water supply system was under construction. A third stage will be implemented in 2007 and a master plan for safe water adduction will be designed during the year. In January 2007, UNHCR and the World Food Programme (WFP) sent a joint assessment mission to Tindouf to verify the food requirements of the Saharan refugees for the coming two years. The mission recommended that the refugees should continue to receive emergency food assistance. Pending a registration of refugees, the caseload would be established at 90,000 beneficiaries. In line with the recommendation of the mission, 35,000 supplementary rations would also be distributed to women of child-bearing age, malnourished children under 5 years and schoolchildren, in order to address serious problems of chronic malnutrition and anaemia among these particularly vulnerable sectors of the camps´ population. The food pipeline has been very fragile since September 2006, when the food security stock in Rabouni, Algeria, was liquidated and not replaced, due to lack of funding. Over 8,000 metric tonnes of food commodities for the refugee camps are required for the coming six months, but funding has not yet been pledged. I call upon donors to contribute generously to the Saharan refugee assistance programme, including the feeding operation, in order to make the living conditions of the refugees tolerable and to prevent further interruptions in their food distribution.

FINANCIAL ASPECTS

OF MINURSO (from UN

Secretary-General's

Report S/2007/202 of April 13, 2007 - paragraphs 45/46) As at 31 December 2006, unpaid assessed contributions to the special account for MINURSO amounted to $52.1 million. As a result of the outstanding assessed contributions, the Organization has not been in a position to reimburse the Governments providing troops for the troop costs incurred since April 2002. The total outstanding assessed contributions for all peacekeeping operations as at 31 December 2006 amounted to $1,889.6 million. DEVELOPMENT OF THE COUNTRY (figures include together Morocco and Western Sahara) According to the African Development Bank, the GDP of Morocco accounts for 7% of the African continent. Morocco is the fifth economic power of Africa with a 2006 GDP of $152.5 billion at PPP ($58.1 billion at official exchange rates), after South Africa, Egypt, Algeria and Nigeria (2001 est.).

Morocco's largest

industry is the mining of

phosphates. Its second largest

source of income is from nationals

living abroad who transfer money to

relatives living in Morocco. The

country's third largest source of

revenue is tourism.

Morocco ranks among the world’s largest producers and exporters of cannabis, and its cultivation and sale provide the economic base for much of the population of northern Morocco. The cannabis is typically processed into hashish. This activity represents about 0.5% of Morocco's Gross Domestic Product (GDP). A UN survey estimated cannabis cultivation at about 1,340 square kilometres in Morocco's five northern provinces. This represents 10 % of the total area and 27 per cent of the arable lands of the surveyed territory and 1.5 per cent of Morocco's total arable land.

Morocco has signed

Free Trade Agreements with the

European Union (to take effect 2010)

and the United States of America.

The United States Senate approved by

a vote of 85 to 13, on July 22,

2004, the

US-Morocco Free Trade Agreement,

which will allow for 98% of the

two-way trade of consumer and

industrial products to be without

tariffs. The agreement entered into

force in January 2006. SOURCES Alertnet BBCnews GEES - Grupo de Estudios Estratégicos HIIK - Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research ICG - International Crisis Group ICRC - International Committee of the Red Cross Le Monde Diplomatique Reuters USIP - United States Institute of Peace UNPO - Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization Warnews Wikipedia |

Morocco has a total population of 382,617 as of July 2007. Western Sahara has a total population of 382,617 as of July 2007 (70,000 of them might be Saharawis, 150,000 might be Moroccan troops, the rest Moroccans who entered the territory during the occupation). The Polisario declares the number of Saharawi population in the camps to be approxi-mately 155,000. Morocco disputes this number, saying it is exaggerated for political reasons and for attracting more foreign aid. On September 1, 2005, the number of assisted beneficiaries was reduced from 158,000 to 90,000 "most vulnerable".Because of the political situation, there are no correct demo-graphic statistics concerning the sole Western Sahara. Even not the UNHCR provides trustable statistics concerning the refugee camps. The major ethnic group of the Western Sahara are the Saharawis, a nomadic or Bedouin tribal or ethnic group speaking Hassaniya dialect of Arabic, also spoken in much of Mauritania. They are of mixed Arab-Berber descent, but claim descent from the Beni Hassan, a Yemeni tribe supposed to have migrated across the desert in the 11th century. Physically indistingui-shable from the Hassaniya speaking Moors of Mauritania, the Saharawi people differ from their neighbours partly due to different tribal affiliations (as tribal confedera-tions cut across present modern boundaries) and partly as a conse-quence of their exposure to Spanish colonial domination. Surrounding territories were generally under French colonial rule. Like other neighbouring Saharan Bedouin and Hassaniya groups, the Saharawis are Muslims of the Sunni sect and the Maliki law school. Both Hassaniya Arabic and Moroccan Arabic are spoken, together with French and Spanish.Western Sahara depends on pastoral nomadism, fishing, and phosphate mining as the principal sources of income for the population. The territory lacks sufficient rainfall for sustainable agricultural production, and most of the food for the urban population must be imported. Incomes in Western Sahara are substantially below the Moroccan level. The Moroccan Government controls all trade and other economic activities in Western Sahara. Morocco and the EU signed a four-year agreement in July 2006 allowing European vessels to fish off the coast of Morocco, including the disputed waters off the coast of Western Sahara. (CIA) For political reasons, no separated statistics are available about GDP (PPP) and poverty. Anyway it is possible to say that all the Saharawi refugees live in poverty as the area east of the Moroccan defensive wall is mainly uninhabited. There is practically no economical infrastructure and the only activity is camel herding kept by Bedouins who depend on pastoral nomadism. Refugees live on the UN World Food Programme. The government-in-exile of the Polisario front has signed oil contracts of its own, but there is no practical exploration. Statistics of Morocco (including Western Sahara, so-called Southern Provinces)

GDP (PPP) (2006

est.)(CIA)

HDI

Poverty 19.0% of the population live below national poverty line (CIA/2005) Unemploy-ment rate 7.7% (2006 est.)(CIA)

Child labour

11% (5-14 year olds) (1999-2004) (UNICEF) Under-five mortality rate (2006) 43‰ (UNDP) Military ex-penditures 5.0% of GDP (2003)(CIA)

Sources |

After

Israeli advice and assisted by a billion dollar pay-out from the

USA, between 1981-1987 Morocco built the so-called

After

Israeli advice and assisted by a billion dollar pay-out from the

USA, between 1981-1987 Morocco built the so-called