| |

Secessionist insurgency

in south Philippines

– 1969/2008

updated at

February 2008

|

Source ©

Wikipedia |

The Philippines,

officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an archipelagic

nation located in Southeast Asia, with Manila as its capital city.

The Philippine Archipelago comprises 7,107 islands in the western

Pacific Ocean, of which only c. 400 are permanently inhabited.

The Philippines is among the world's most populous

countries. There are more than 11 million overseas Filipinos

worldwide, about 11% of the total population.

The Philippines has

many affinities with the Western world, derived mainly from the

cultures of Spain, Latin America, and the United States. Roman

Catholicism became the predominant religion, although the

pre-Hispanic indigenous religious practices and Islam continue to

flourish.

|

THE CONFLICT AT A GLANCE

The confrontation between Philippine

government and Muslim secessionists on the southern island of Mindanao,

which began in 1969, have caused 120,000 deaths and displaced up to 2

million people.

The Mindanao

conflict is deeply rooted in the colonial

history of the country. Muslims arrived in the

Philippines in the 13th century. Mindanao, the

southernmost of the country's three regions, was

ruled by Muslim sultanates well before Spanish

Christians arrived in the second half of the

16th century, finding strong opposition to their

rule in the Muslim area. When the Philippines passed from

Spanish to American colonial rule at the end of

the Spanish-American War in 1898, large areas of

the Muslim south remained untouched. A process

of forced economic and political integration

started

in the first decades of the 20th century. After

independence, in 1946, the government encouraged Catholic

settlers to move from the north to resource-rich

Mindanao, displacing the comparatively poorer

Muslim communities.

The modern conflict flared at the end of the 1960s when the

Muslim minority - known as the Moros - launched

an armed struggle for their ancestral homeland

in the south of Philippines, the so-called

Bangsamoro.

But over the years, the Moro campaign for

self-rule has become only one of several sources

of bloodshed on Mindanao. These include a long

Maoist insurgency, violence linked to militant

Islamist groups with pan-Asian aspirations,

bloody ethnic vendettas, clan wars and banditry.

In 1996 the government gave predominantly Muslim

areas a low degree of self-rule, setting up the

Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM),

which was generally considered an insufficient

improvement.

Recently, significant progress

has been made in peace negotiations with the two

main Muslim separatist organisations, the MNFL

and the MILF, but Mindanao and neighbouring

islands remain an attractive refuge for radical

jihadist

groups.

Today more

than 120,000 people remain uprooted by the

fighting, an estimate considered to be

conservative.

Politics and

religion aside, much of the violence is fuelled

by deep poverty rooted in decades of

under-investment.

Today poverty is considered at the same time a

cause and a consequence of the war.

Estimates of economic losses due

to the Mindanao conflict range from P5 billion to P10 billion

annually from 1975 to 2002. |

Politics

The Philippines has a representative democracy modelled on

the US system. The 1987 constitution re-established a presidential

system of government with a bicameral legislature and an independent

judiciary. The president is limited to one six-year term. Provision

also was made in the constitution for autonomous regions in Muslim

areas of Mindanao and in the Cordillera region of northern Luzon,

where many aboriginal tribes still live.

(Source: US Department of State)

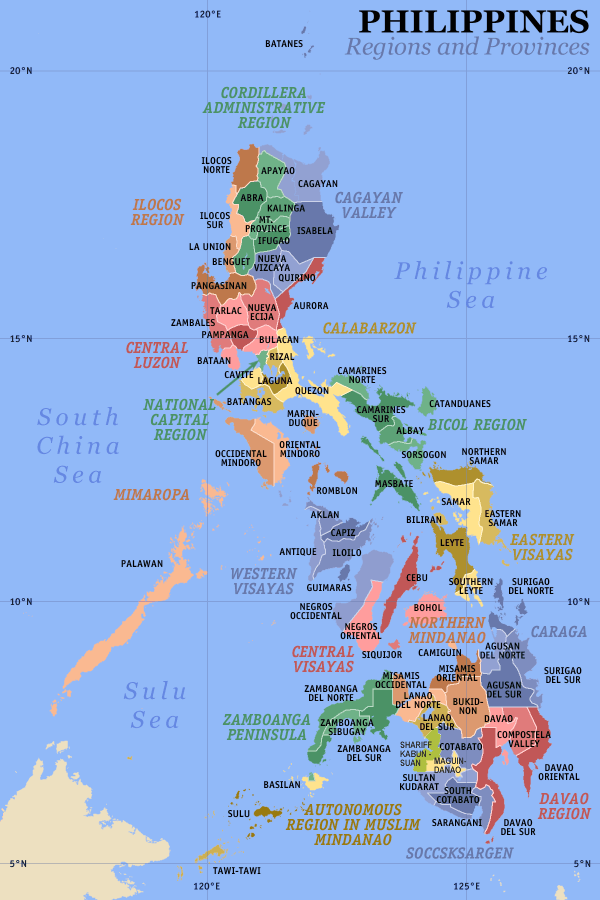

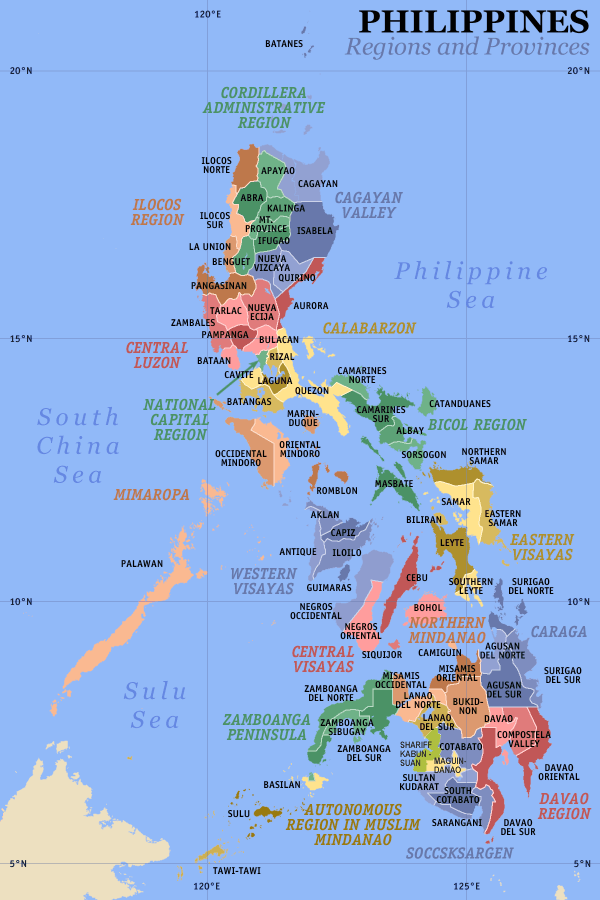

The

Philippines is divided into three island groups :

Luzon,

Visayas, and

Mindanao. These are divided into

17 regions,

81 provinces,

131 cities,

1,497 municipalities, and 41,994

barangays.

On

July 24,

2006, the

State of the Nation Address of

President

Arroyo announced the proposal to create five

economic

super regions to concentrate on the economic

strengths in a specific

area.

|

TYPE OF CONFLICT

Secessionist insurgency demanding

the formation of an independent Moro Islamic

state

in

the southern portion of

Mindanao, the

Sulu Archipelago and

Palawan.

Historically, the Moro people had settled the geographical areas we

now describe as Mindanao, the islands of Basilan and Palawan,

and Sulu and Tawi-Tawi archipelago.

Read on

Moro people,

Bangsamoro,

the Sabah

dispute

and the

Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao.

FIGHTING FACTIONS FROM LATE 1960s TO 2007

1) Philippines government, led in the last years by President

Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo,

mainly supported by US Army, Christian

militias

and

pro-government Muslim militias.

2) Several Islamic groups acting with separate goals:

Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF)

Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF)

Abu Sayyaf (ASG)

Jemaah Islamiyah (JI)

Al

Qaeda-inspired groups (i.e. Rajah Soliman Movement, Abu Sofia, etc.)

«

The first thing we need to do in order to understand the complex

issue involved in the present Mindanao War is to distinguish the

different Muslim actors. This is NOT a popular view, because from

the Presidency to the people in the street, there is a natural

proclivity to adopt a simplistic view of the complex issue and thus

advocate for simplistic solution such as the prevailing "all out

military solution" expressed in various slogans like: "final

solution," "total war,"... »

By this words starts one of the many interesting articles on the

conflict in Mindanao, which explain some aspects of such a complex

matter.

Some articles are available here:

Mindanao Peace process

(1996)

Important Considerations Regarding the War in Mindanao … (2001)

The Mindanao Peace Process

(2004)

Philippines

terrorism: the role of militant Islamic converts

(2005)

“Radical Muslim Terrorism” in the Philippines

(2006)

New People's Army (NPA) is a Maoist paramilitary group

fighting for communist revolution in the Philippines.

Read on

militias

CASUALTIES

According to Reuters AlertNet, an estimated 120,000 have died from

the late 1960s (up to 50% of them were noncombatants) and, time by time, an estimated 2 million people

were internally displaced.

In total, armed incidents have displaced between 119,600 and 139,600

people in Mindanao between January and September 2007

(Internal

Displacement Monitoring Centre).

Read on

internally displaced people

WEAPONS' SUPPLIERS

The Philippines government currently receives arms by USA and South Korea,

according to ARMSFLOW.

Philippine military is accused by observers of igniting the conflict

to promote military demands for updating their weaponry and

equipment. British arms companies were poised to offer war materiel

to the Philippine military.

Read on

guerrilla warfare

and

arms industry

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The conflict began in the late

1960s when a political organisation called MNLF began fighting for a

Moro Muslim homeland (Bangsamoro),

which includes the southern portion of

Mindanao, the

Sulu Archipelago and

Palawan.

The struggle is rooted to the

conflicts caused by Spanish and US colonisation, beginning in 1521.

However, religion is but one difference, even if a large one,

between the so-called

Moro people

and the rest of

Filipinos. Culture, language, and

tradition are also divisive.

On a larger scale, the Muslim

insurgency in the Philippines is an outgrowth of the division of the

Malay Archipelago by European and American colonial powers. The

colonies that became the nations of

Indonesia,

Philippines,

Malaysia, and

Thailand lumped together and split indigenous peoples of

hundreds of languages and cultures into modern western-like nations,

trying to

assimilate them into "nationalities." There is no doubt that all

of these indigenous groups have suffered immeasurably to avoid

destruction of their culture, language, and livelihood.

At its root, the Moro insurgency is a struggle against the

“historical and systematic marginalization and minoritization of the

Islamized ethno-linguistic groups, collectively called Moros, in

their own homeland in the Mindanao islands”. From 76 percent of the

Mindanao population in 1903, Muslim groups accounted for no more

than 19 percent in 1990.

The conflict might be viewed as a clash between two imagined nations

or nationalisms, Filipino and Moro, each with their own narratives

of the conflict.

Politics, history and religion aside, it must be

said that much of the

present violence is fuelled by deep poverty rooted in decades of

under-investment in the region.

Early history

The

Negritos are believed to have migrated to the Philippines

by land bridges some

30,000 years ago from Borneo, Sumatra, and Malaya. The Malays

followed in successive waves. These people belonged to a primitive

epoch of Malayan culture, which has apparently survived to this day

among certain groups such as the Igorots. The Malayan tribes that

came later had more highly developed material cultures.

The term Negrito refers to a small-statured,

dwindling ethnic group which is now restricted to isolated parts of

Southeast Asia. Negritos are arguably the most enigmatic people

on our planet as they belong to an ancient stratum of

Homo sapiens in Asia. No other living human population has

experienced such long-lasting isolation from contact with other

groups.

[1] Their current populations include the

Aeta,

Ati and at least 25 other tribes of the

Philippines, the

Semang of the

Malay peninsula, the

Mani of

Thailand and 12

Andamanese tribes of the

Andaman Islands.

"Negrito" is the

Spanish diminutive of

negro, i.e. "little black person", referring to their small

stature, and was coined by early European invaders and explorers who

assumed that the Negritos were from Africa. Occasionally, some

Negritos are referred to as

pygmies, bundling them with peoples of similar physical stature

in Central Africa.

The Malay people are believed to have

originated in Borneo and then expanded outwards into Sumatra and

later into the Malay Peninsula.

The social and political organization of the

population, in the widely scattered islands, evolved into a

generally common pattern. Only the permanent-field rice farmers of

northern

Luzon had any concept of territoriality. The basic unit of

settlement was the

barangay, originally a kinship group headed by a

datu (chief). Within the barangay, the broad social divisions

consisted of the maharlika (nobles),

including the datu; timawa (freemen);

and a group described before the Spanish period as dependents.

Dependents included several categories with differing status:

landless agricultural workers; those who had lost freeman status

because of indebtedness or punishment for crime; and alipin

(slaves), most of whom appear to have been war captives.

The Philippines had cultural and trade relations

with India, China, and Islamic merchants as early as the 9th

century.

In the 13th century Arab traders from

Malay, Borneo and the

Indonesian islands started introducing

Islam into the southern islands.

By the 13th century, Islam was established in the

Sulu Archipelago and spread from there to

Mindanao; it had reached the area of modern Manila by 1565.

Although Islam spread as far north as

Luzon, animism was still the religion of the

majority of the Philippine islands. Muslim immigrants introduced a

political concept of territorial states ruled by

rajas or

sultans who exercised

suzerainty over the datu. Neither the political state concept of

the Muslim rulers nor the limited territorial concept of the

sedentary rice farmers of Luzon, however, spread beyond the areas

where they originated.

Before the arrival of the Spanish colonialists

the

Bangsamoro

was already in the process of state formation and governance. In the

middle of the 15th century Sultan Shariff ul-Hashim

established the Sulu Sultanate followed by the establishment of the

Magindanaw Sultanate in the early part of the 16th century by

Shariff Muhammad Kabungsuwan. Their experience on state formation

continued with the establishment of the Sultanate of Buayan, the Pat

a Pangampong ko Ranao (Confederation of the Four Lake-based

Emirates) and other political institutions. These states were

already engaged in trade and diplomatic relations with other

countries, including China. Administrative and political systems

based on the realities of the time existed in those states. In fact,

it was with the existence of this well-organized administrative and

political system that the Bangsamoro people managed to survive the

military campaigns against them by Western colonial powers for

several centuries and preserve their identity as a political and

social entity.

When the

Spanish arrived in the 16th century, an estimated 500,000 people

lived in the Philippines area.

The first Europeans to visit (1521) the

Philippines were those in the Spanish expedition around the world

led by the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan. Other Spanish

expeditions followed, including one from New Spain (Mexico) under

López de Villalobos, who in 1542 named the islands for the infante

Philip, later Philip II.

Spanish

colonisation

The conquest of the Filipinos by Spain did not begin in earnest

until 1564, when another expedition from New Spain, commanded by

Miguel López de Legazpi, arrived. Spanish leadership was soon

established by violence and destruction over many small independent

communities that previously had known no central rule.

By 1571, López de Legazpi

established the Spanish city of Manila on the site of a Moro town he

had conquered the year before to the

Tagalog

Muslim king,

Rajah Suliman. Then

the Spanish foothold in the

Philippines was secure, despite the opposition of the Portuguese,

who were eager to maintain their monopoly on the trade of East Asia.

Manila repulsed the attack of the Chinese

pirate Limahong in 1574. For centuries before the Spanish arrived

the Chinese had traded with the Filipinos, but evidently none had

settled permanently in the islands until after the conquest. Chinese

trade and labor were of great importance in the early development of

the Spanish colony, but the Chinese came to be feared and hated

because of their increasing numbers, and in 1603 the Spanish

murdered thousands of them (later, there were lesser massacres of

the Chinese).

The Spanish governor, made a Viceroy in 1589, ruled with the advice

of the powerful royal audiencia. There were frequent uprisings by

the Filipinos, who resented the encomienda system.

The encomienda system was a

trusteeship labor system employed by the Spanish crown during

the

Spanish colonization of the Americas and the

Philippines in order to consolidate their conquests.

Conquistadors were granted trusteeship over the

indigenous people they conquered, in an expansion of familiar

medieval

feudal institutions. The maximum size of an encomienda was three

hundred Amerindians, although they were usually much smaller. The

encomenderos were similar to feudal lords in that they were entitled

to demand tribute from the people under their care in the form of

specie, kind, or corvee, but differed in that they were not given

juridical authority. In exchange for the right to collect this

tribute, the encomenderos were charged with maintaining order

through an established military and providing instruction in

Catholicism. As European disregard for the Amerindians led to

widespread corruption and abuses, the system that was intended to

assist in the evangelization of the Natives and the establishment of

a stable society became a force for oppression and enslavement.

Although the Crown reserved the right to revoke an encomienda from

the hands of an unjust encomendero, it rarely did.

By the end of the 16th century Manila had become a leading commercial

center of East Asia, carrying on a flourishing trade with China,

India, and the East Indies. The Philippines supplied some wealth

(including gold) to Spain, and the richly laden galleons plying

between the islands and New Spain were often attacked by English

freebooters. There was also trouble from other quarters, and the

period from 1600 to 1663 was marked by continual wars with the

Dutch, who were laying the foundations of their rich empire in the

East Indies, and with Moro pirates. One of the most difficult

problems the Spanish faced was the subjugation of the Moros.

Intermittent campaigns were conducted against them but without

conclusive results until the middle of the 19th cent.

The term “Moro” was the appellation

applied to all the Muslim population of Southeast Asia by the

Portuguese who seized Melaka in 1511. The Moros are today a

multilingual ethnic group and they mostly live in a region dubbed as

Bangsamoro in the southern Philippines. Bangsamoro was

originally home to the Muslim sultanates of Mindanao (such as

Maguindanao and

Sulu).

Although

Spain claimed the territories of Moros prior to the

Spanish-American War, the Spanish had little actual control over the

area. The staunchly Muslim sultanates of the Sulus and Mindanao

fiercely resisted

Spanish colonial rule and consequent attempts at forcible

conversion to

Catholicism, and were therefore not fully integrated with the

rest of the islands. In the face of this stiff resistance, the

Spanish were restricted to a handful of coastal garrisons, and they

made only occasional punitive expeditions into the interior. After a

series of less-than-successful attempts during the centuries of

Spanish rule in the Philippines, Spanish forces captured the city of

Jolo, the seat of the

Sultan of Sulu, in 1876. The Spanish and the Sultan of Sulu

signed the Spanish Treaty of Peace on July 22, 1878. Control of the

Sulus outside of the Spanish garrisons was left in the hands of the

Sultan. The treaty had translation errors: According to the Spanish

language version, Spain had complete sovereignty over the Sulus,

while the

Tausug version described a

protectorate instead of an outright

dependency.

As the power of

the Spanish Empire waned, the Jesuit orders became more influential

in the Philippines and acquired great amounts of property, while the

sultanate was taken by internal struggles and international claims,

aiming to keep as much power as possible more than to protect the

people.

The power of

the clergy together Spanish injustices, bigotry, and economic

oppressions fed

the rising sentiment for independence, greatly inspired by the

brilliant writings of

José Rizal.

José Rizal is

considered a national hero and the anniversary of Rizal's

death is commemorated as a Philippine holiday called Rizal Day.

He was a member of a wealthy mestizo family but he felt limited by

Spanish insistence on promoting only "pure-blooded" Spaniards. He

began his political career at the University of Madrid in 1882 where

he became the leader of Filipino students there. For the next ten

years he traveled in Europe and wrote several novels considered

seditious by Filipino and Church authorities. He returned to Manila

in 1892 and founded

La Liga

Filipina, a political group dedicated to peacefully unite the whole archipelago into one vigorous and homogenous

organization. He was

rapidly exiled to Mindanao. During his absence,

Andrés Bonifacio

and other members of the Liga

founded the revolutionary organization

Katipunan,

dedicated to the violent overthrow of Spanish rule. When the

Philippine Revolution started on August 26, 1896, Rizal was

convicted of rebellion, sedition and of forming illegal association,

condemned and shot dead at Bagumbayan Field.

Andrés Bonifacio y de Castro is regarded as the "Father of

the Philippine Revolution" and one of the most influential national

heroes of his country, eventually given the title of Supremo..

Born to a Tagalog father and a Spanish mestiza mother, he was a

clerk before becoming a nationalist leader and poet.

Just before the Revolution broke out, he formed a revolutionary

government called "Republika ng mga Katagalugan" with himself as the

president. But his personal campaigns were less than successful; he

lost all his battles and all led to heavy casualties and massacres.

The revolutionaries, led by officers coming from the upper classes

as the celebrated

Emilio Aguinaldo, had greater success in

Cavite, temporarily

driving the Spanish out of the area. Thus, they sent out a manifesto

calling for a revolutionary government of their own, disregarding

Bonifacio's leadership.

Bonifacio's birthday on November 30 is celebrated as Bonifacio Day

and is a public holiday in the Philippines.

Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy was a Filipino general, politician,

and independence leader, who played an instrumental role in

Philippine independence during the Philippine Revolution against

Spain and the Philippine-American War that resisted American

occupation. In the Philippines, Aguinaldo is considered to be the

country's first and the youngest Philippine President, though his

government failed to obtain any foreign recognition.

The

Philippine Revolution followed the creation of La Liga

Filipina and the Katipunan.

In 1895, Emilio Aguinaldo joined the Katipunan rebellion as a lieutenant

under Gen.

Baldomero Aguinaldo and rose to the rank of general in a few

months. When, in 1896, 30,000 members of the Katipunan launched an attack

against the Spanish colonizers in the same week, only Emilio

Aguinaldo's troops were successfull.

Bonifacio presided over the

Tejeros Convention in Tejeros, Cavite (deep in Aguinaldo

territory) to elect a revolutionary government in place of the

Katipunan on March 22, 1897. Away from his power base, Bonifacio

unexpectedly lost the leadership to Aguinaldo, and was elected instead to the office of Secretary of

the Interior.

Even the election of Bonifacio as Secretary of the Interior was questioned by an Aguinaldo supporter, claiming Bonifacio had not the

necessary schooling for the job. Insulted, Bonifacio

declared the Convention null and void, and sought to

return to his power base in Rizal. Bonifacio was

charged, tried and found guilty of treason (in

absentia) by a Cavite military tribunal. As a

consequense he

was sentenced to death. Aguinaldo's soldiers caught

up with Bonifacio in the town of Indang. They surrounded the house

and asked Bonifacio and his men to disarm and come out peacefully

but Bonifacio refused and violence followed, during which the

Supremo was wounded. Then Aguinaldo confirmed

the death sentence, and the dying Bonifacio was

hauled to the mountains of Maragondon in Cavite, and

executed on May 10, 1897, even as Aguinaldo and his forces were

retreating in the face of government troops augmented by new

recruits from Spain.

The new Spanish Governor-General

Fernando Primo de Rivera declared, "I can take Biak-na-Bato. Any army can capture it. But I cannot

end the rebellion". Then he offered peace to the revolutionaries. Lawyer

Pedro Paterno volunteered as negotiator between

the two sides. For four months, he travelled between

Manila and Biak-na-Bato. His hard work finally bore

fruit when, on December 14-15, 1897, the

Pact of Biak-na-Bato was signed, which specified

that the Spanish would give self-rule to the Philippines within 3

years if Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo was exiled. In accordance with the

pact, Aguinaldo

and twenty five other top officials of the

revolution were banished to

Hong Kong with 400,000 pesos in their pockets,

that they subsequently used to buy weapons to resume the fight,

while the rest of the men got 200,000 pesos.

However, thousands of other Katipuneros continued to fight the

Revolution against Spain for a sovereign nation. Unlike Aguinaldo

who came from a privileged background, the bulk of these fighters

were peasants and workers who were not willing to settle for

'indemnities.'

American

colonisation

On April 25,

1898, war broke out between Spain and the United States, the

so-called

the

Spanish-American War.

The United States relied greatly

on assistance from Filipino revolutionaries led by Emilio Aguinaldo,

who already controlled much of the countryside and had proclaimed a

Philippine republic when American troops arrived in large numbers in

July. Americans negotiated Spain’s surrender of Manila in August, as

the war ended. But, instead of liberating the Philippines from

Spanish domination, the United States chose to annex the islands and

begin building an American empire.

Following declaration of war,

Commodore George Dewey

sailed from Hong Kong with Emilio Aguinaldo on board,

in the hope he would rally Filipinos against the Spanish colonial

government. Fighting began in the

Philippine islands at the Battle of Manila Bay on May 1, where

Commodore Dewey destroyed the Spanish fleet. However, he did not

have enough manpower to capture Manila and so Aguinaldo's guerrillas

made the big job and took control of the

entire island of Luzon, except for the walled city of

Intramuros. On

June 12,

1898, Aguinaldo declared the independence of the Philippines.

Then 15,000 US troops arrived at the end of July. Although a peace

protocol was signed by the two belligerents on August 12, Commodore

Dewey and Maj. Gen. Wesley Merritt, leader of the army troops,

assaulted Manila the very next day, unaware that peace had broken

out, and captured the city.

This battle marked an end of Filipino-American

collaboration, as Filipino forces were prevented from entering the

captured city of Manila, an action which was deeply resented by the

Filipinos and which later led to the

Philippine-American War.

On

June 12, 1898, Filipino revolutionary forces under General

Emilio Aguinaldo proclaimed the sovereignty and independence of the

Philippines from the colonial rule of Spain. The formal

Philippine Declaration of Independence proclamed by the

Dictatorial Government of the Philippines of Emilio Aguinaldo

essentially placed the Philippines under the protection of the

United States, so that it was later modified by another

proclamation. The dictatorial government then in place was replaced

by a revolutionary government headed by Emilio Aguinaldo as

president on June 23, 1898.

The

First Philippine Republic, officially República Filipina was

established on January 23, 1899, with the proclamation of the

Malolos Constitution.

Then Aguinaldo and his men fled to Northern Luzón, trying to resist

the American occupation. The US combined tactics of pacification

and social improvement with brutal military strikes and finally

Aguinaldo was captured on March 23, 1901.

On April 1, 1901, Aguinaldo announced allegiance to the

United States, formally ending the First Republic and the

Philippine-American War, recognizing the sovereignty of the United

States over the Philippines. Some non-organized hostilities

continued anyway until the battle Bud Bagsak in 1913.

The

Treaty of Paris

was signed on December 10, 1898, ending the Spanish-American War only 109

days after the outbreak. Spain ceded to the

US, for $20 million, Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Caroline Islands, Guam

and the entire Philippines, despite the controversial

situation created in 1878 with the Sultan of Sulu concerning

protectorate or dependency of the Moro territories. Included in this cession were the

territories of Mindanao and Sulu, which actually had not been in

full Spanish control. About two years later, on November 7, 1900,

the US paid an additional $100,000 to Spain to include in the 1898

cession the Sulu islands stretching as far west as Sibutu and

Cagayan de Sulu.

Following the Treaty of Paris, the Americans asked

the Sultan of Sulu, Jamalul Kiram II, to recognize the US in the

place of Spain, and honor the 1878 provisions of the treaty, which

the Sultan had signed with Spain. As first, the Sultan refused,

stating that the US was a different entity. But the Sultan was not

supported by his ruling council and after few months

he had

to concede to the Americans.

In place of the Spanish treaty,

the Sultan presented Brig. General John Bates with a 16-point

proposal.

The proposal allowed the US to fly its flag side by side with the

Sultanate's and required the US to continue monthly payments to

the Sultan and his datus. The US was not to occupy any of the land

without the permission of the Sultan.

The Sultan's proposal was rejected by Bates, because it did not

acknowledge US sovereignty.

Bates then countered with his 15-point proposal, which included the

recognition of US sovereignty over Sulu and its dependencies, the

guarantee of non-interference with Moro religion and customs and a

pledge that the "US will not sell the island of Jolo or any other

island of the Sulu Archipelago to any foreign nation without the

consent of the Sultan."

The sultan resisted Bates's offer for several months, but he could

not get unanimous support from his ruma bichara (ruling council) to

press for his demands to the Americans. Because of this internal

dissension, led by his own prime minister and adviser Hadji Butu and

two of his top ranking datus, Datu Jolkanairn and Datu Kalbi, the

sultan conceded to the Americans. Officially, Hadji Butu cooperated

with the Americans and "advised his people to accept American rule,

for the sake of peace and to prevent unnecessary loss of lives and

property in Sulu" (Senate of the Philippines).

In February 1899, Aguinaldo led a new revolt, this time against US

rule. Defeated on the battlefield, the Filipinos turned to guerrilla

warfare.

On May 19, 1899, while the forces of the First Philippine Republic

under President Emilio Aguinaldo were resisting the

American invaders, two American battalions occupied Jolo. The

following month, on August 20, Hadji Butu, representing Sultan

Jamalul Kiram II, concluded a treaty with General John C. Bates.

According to this so-called “Bates Treaty,” the Sultan of Sulu

recognized American sovereignty and, in return, the United states

recognized the sultanate as an American protectorate and agreed to

respect the Islamic religion and customs (including polygamy and

slavery) of the Taosug people and not to cede or sell Sulu or any

part of it to any foreign country.

This treaty was based on the earlier Spanish treaty, and it retained

the translation error: the English version described a complete

dependency, while the Tausug version described a protectorate.

Article I of the Treaty in the Tausug version states "The support,

aid, and protection of the Jolo Island and Archipelago are in the

American nation," whereas the English version read "The sovereignty

of the United States over the whole Archipelago of Jolo and its

dependencies is declared and acknowledged."

Although the Bates Treaty granted more powers to the Americans than

the original Spanish treaty, the treaty was still criticized in

America for granting too much autonomy to the Sultan, particularly

concerning the practice of slavery.

The Bates Treaty did not last very long. After the US had

completed its goal of suppressing the resistance in northern

Philippines, it unilaterally abrogated the Bates Treaty on March 2,

1904, claiming the Sultan had failed to quell Moro resistance and

that the treaty was a hindrance to the effective colonial

administration of the area. Payments to the Sultan and his datus

were also stopped.

Bates later admitted that the treaty was merely a stop-gap measure,

signed only to buy time the war in the north was ended and more

forces could be brought to bear in the south.

On October 10, 1904,

Hadji Butu

was appointed by the American military authorities as assistant to

the Military Governor of the province.

Subsequently, on June 20, 1913, General John J. Pershing (Military

Governor of the Moro Province) promoted him as Deputy District

Governor of Sulu.

In December, 1915, Hadji Butu was appointed by Governor-General

Francis Burton Harrison as senator, representing the 12st Senatorial

District (Mindanao and Sulu). He was thus the first Muslim to sit in

the Philippine Senate.

Hadji Butu proved to be an able parliamentarian so that he was

re-appointed senator by Governor-General Henry L. Stimson in 1928.

Many Americans strongly opposed this new trend of

imperialism and the annexion of the new territories hardly passed in

the Congress. Then Theodore Roosevelt became the twenty-sixth US

president after the assassination of William McKinley in 1901.

Roosevelt strongly supported American expansionism, and increased

the size of the military to implement it. His policy was epitomized

in the phrase, “Speak softly, but carry a big stick."

On July 4, 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt issued a

proclamation declaring an end to the Philippine Insurrection and a

cessation of hostilities in the Philippines "except in the country

inhabited by the Moro tribes, to which this proclamation does not

apply."

On June 1, 1903, the

Moro Province

was created, which included "all of the territory of the Philippines

lying south of the eighth parallel of latitude, excepting the island

of Palawan and the eastern portion of the northwest peninsula of

Mindanao". English was declared the official language. Six

hundred American teachers were imported aboard the USS Thomas.

Although a Filipino was always appointed chief justice, the majority

of the members of the Supreme Court were Americans. Also, the

Catholic Church was disestablished, and a substantial amount of

church land was purchased and redistributed. Some measures of

Filipino self-rule were allowed, however. The province had a civil government, but many civil

service positions, including the district governors and their

deputies, were held by members of the American military. This system

of combined civil and military administration had several

motivations behind it. One was the continued Moro hostilities.

Another was the Army's experience during the Indian Wars, when it

came into conflict with the civilian

Bureau of Indian Affairs. A third was that the Moros, with

their feudal society, would have no respect for a military leader

who submitted to the authority of a non-combatant.

Although determined to impose direct rule, the US Army moved

cautiously to avoid encouraging widespread Moro opposition. The US

Government preferred that the Army take control without the

bloodshed that had characterized the recently concluded war against

Filipino nationalists. The Philippine Commission announced that the

United States would not interfere with tribal organization and

culture, and US officials made it clear they would not seek to

convert the Moros to Christianity

But the new Governor of the Moro Province,

Major General Leonard Wood, had to face the Moro propensity for blood feuds,

polygamy, and human trafficking. He wanted to bring them the

American "high ideals of civilization" as soon as possible. (Andrew

J. Bacevich,

What happened at Bud Dajo, The Boston Globe, March 12, 2006).

He instituted many reforms:

-

On Woods'

recommendation, the United States unilaterally

abrogated the Bates Treaty, citing continuing

piracy and attacks on American personnel. The

Sultan of Sulu was demoted to a purely religious

office, with no more power than any other datu,

and was provided with a small salary. The United

States assumed direct control over Moroland.

-

Slavery was

abolished. Slave trading and raiding were

repressed, but slaves were left with their

owners. Wood announced that slaves were "at

liberty to go and build homes for themselves

wherever they like[d]," and pledged the

military's protection for any former slaves that

did so. Similar actions had been taken by

individual commanders in the past, but Wood's

edict had the backing of the Moro Council,

giving it more permanent weight.

-

The Cedula

Act of 1903 created an annual registration poll

tax. This registration poll tax was highly

unpopular with the Moros, since they interpreted

it as a form of tribute. According to Hurley,

participation in the Cedula was very low as late

as 1933.

-

The legal

code of Moroland was reformed. Disputes between

Moros and non-Christians had been left to Moro

laws and customs, with Philippine laws only

applying to disputes with Christians. This led

to a double standard, with a Moro who killed a

Christian facing a stiff prison sentence, but

with a Moro who killed another Moro facing only

a maximum fine of 150 pesos. Wood attempted to

codify Moro law, but there was simply too much

variance in laws and customs between the

different tribes and even between neighboring

cottas. Wood placed the Moros underneath the

Philippine criminal code, but actual enforcement

of this proved difficult.

-

Private land

ownership was introduced, in order to help the

Moros transition to a more individualistic

society from their traditional tribal society.

Each family was given 40 acres (16 ha) of land,

with datus given additional land in accordance

with their status. Land sales had to be approved

by the district governments in order to prevent

fraud.

-

An

educational system was established. By June

1904, there were 50 schools with an average

enrollment of 30 students each. Because of

difficulties in getting teachers that spoke

native languages, classes were conducted in

English after initial training in that language.

Many Moros were suspicious of the schools, but

some offered buildings for use as schools.

-

Trade was

encouraged in order to give the Moros an

alternative to fighting. Trade had been

discouraged by banditry, piracy, and the

possibility of inter-tribal disputes between

Moro merchants and local customers. When trading

with foreign merchants, a lack of warehousing

made for a buyer's market, leading to low

prices. Wood handled banditry and piracy by

establishing military posts at river mouths in

order to protect sea and land routes. Starting

with a pilot project in

Zamboanga, a system of Moro Exchanges were

established. These exchanges provided Moro

traders with warehouses and temporary housing in

exchange for honoring a ban on fighting within

the exchange. Bulletin-boards listed market

prices in

Hong Kong and

Singapore, and the district governments

guaranteed fair prices. These Exchanges proved

highly successful and profitable, and provided a

neutral ground for feuding datus to settle their

differences.

Not surprisingly, Wood’s policies met with increased

opposition. The elimination of slavery and the traditional legal

code struck directly at the power of the datus, and some of them

decided to take up arms against the Americans. Other Moros chose to

resist for religious reasons, fearing the Americans would eventually

demand that they convert to Christianity. The Cedula Act also

created intense resentment among many Moros who saw compliance as a

form of tribute to a non-Islamic government.

On the other hand, the cultural difference between Americans and

Moros was too big and the mentality of Indian Wars ("the only

good Indian is a dead Indian", US Gen. Philip Sheridan, 1869)

easily came to Philippines. "Civilize 'em with a Krag" became

a similar catchphrase (the Krag was the rifle used at that time by

the US Army).

The

Moro rebellion

took several forms even if the American occupation forces did not

face a unified insurgency or nationalistic movement, but rather the

forces of individual datus who refused to accept American control as

well as localized popular uprisings.

Some Moros, especially on heavily forested Mindanao, practiced

guerrilla warfare, raiding US encampments for weapons and setting

ambushes on jungle trails. The most unnerving form of Moro

resistance was the juramentado, or suicide attack. A juramentado

attacker would seek to reach paradise by slaying as many

nonbelievers as possible before being killed himself. Such attacks

were not common, but they occurred often enough to keep the

Americans on edge.

The Moro rebellion was an ugly war, poorly armed Moro warriors

against seasoned US Army regulars. The Moro weapon of choice was the

kris, a short sword with a wavy blade; the Americans used

Springfield rifles and field guns. Obviously, the Americans never

lost an engagement. Yet even as they demolished one Moro stronghold

after another and wracked up an impressive body count, the fighting

persisted.

Modern Muslim inhabitants of the southern Philippines see the Moro

Rebellion as one phase of a continuing struggle against non-Muslim

influences, the Spanish, the Americans, and the central government

of the Philippines.

To keep full control of the Moro territory, Wood

engaged in strong military actions against the rebels but the usual

result of the indiscriminate firing by US soldiers was the killing

of women and children and burning houses and crops. Any punitive

expeditions left people without homes or food, children without

parents, clans without leaders, and contributed to the breakdown of

the Moro social order.

A long chain of events brought to the

First Battle of Bud Dajo, in which 790 American troops armed

with artillery and rifles attacked a village of rebels hidden in the

crater of the dormant volcano Bud Dajo, killing 600 up to 1,000 men,

women and children and suffering as many as 18 casualties.

Although the battle was a victory for the American forces, it was

also an unmitigated public relations disaster.

In late 1905, hundreds of Moros-determined to

avoid paying the cedula head tax, which they considered

blasphemous-began, took refuge on the peak of Bud Dajo, a volcanic

crater on the island of Jolo, in the Southern Philippines.

Refusing orders to disperse, they set themselves up as ''patriots".

In response Wood dispatched several battalions of infantry to Bud

Dajo with orders to ''clean it up." On March 5, 1906, the

reinforcements arrived and laid siege to the heights. The next day,

they began shelling the crater with artillery. At daybreak on March

7, the final assault commenced, the Americans working deliberately

along the rim of the crater and firing into the pit. When the

action finally ended some 24 hours later, the extermination of as

many as 1,000 Filipino Muslims had been accomplished. Only six of

them survived in front of 15 to 18 American casualties.

Among the dead laid several hundred women and children.

On February 1, 1906, Major Gen.

Tasker H.

Bliss replaced Wood as Governor of Moro Province. He preferred

diplomacy to coercion and opened a "peace era," at the price of

tolerating a certain amount of lawlessness. His new reforms reduced

crime and promote agriculture and trade but law enforcement in the

Moro Province remained difficult.

An elected Filipino

legislature was established in 1907. On February 1, 1906, Major Gen.

Tasker H.

Bliss replaced Wood as Governor of Moro Province. He preferred

diplomacy to coercion and opened a "peace era," at the price of

tolerating a certain amount of lawlessness. His new reforms reduced

crime and promote agriculture and trade but law enforcement in the

Moro Province remained difficult.

An elected Filipino

legislature was established in 1907.

In 1909 Bliss was replaced by Brigadier General

John J.

Pershing, who largely adhered to the policies Bliss had put in place

and didn't practice collective punishment. But his 1911 decision to

disarm the population enraged many Moros and opened a new period of

conflict. In late 1911 about 800 Moros fled to the old battleground

of Bud Dajo to make a stand but Pershing succeeded in dispersing

them ("only" 12 Moro were killed), thanks to a patient approach and

to the cooperation of some Moro leaders.

In 1913 thousands of Moros moved to the fortified crater of

Bud Bagsak in eastern Jolo to defy the disarmament policy. Pershing

tried to negotiate a pacific solution but a group of around 500

remained in their stronghold and refused to surrender their weapons.

Unwilling to accept such open defiance and under pressure to end the

insurgency, Pershing ordered an attack on Bud Bagsak that resulted

in the deaths of almost all the Moros who were there, including as

many as 50 women and children.

During the Moro Rebellion, the Americans suffered clear cut

losses, amounting to 130 killed and 323 wounded. Another 500 or so

died of disease. The Philippine Scouts who augmented American forces

during the campaign suffered 116 killed and 189 wounded. The

Philippine Constabulary, a local police force, suffered heavily

as well, more than 1,500 losses sustained, half of which fatalities.

On the Moro side, losses were remarkably high, with several thousand

killed and wounded. Estimates range from 10,000 to well over 20,000

killed, with an unknown number of wounded. (Wikipedia,

Moro rebellion)

The

battles at places like Bud Dajo and Bud Bagsak long ago faded from

the consciousness of Americans—in fact, they were not much noticed

by Americans even at the time. Among the Moros, however, the US

campaigns were of major importance. The high Moro death tolls

resulting from US military operations contributed to the

development of an anti-US sentiment that continues today. That

sentiment became obvious in February 2003 when the Philippine

Government announced it would participate in Operation Balikatan, a

joint exercise with the United States on Jolo. The government’s

announcement provoked loud condemnations from many Filipinos,

including nationalists who feared the United States would use the

exercise as a way to become directly involved in combat against the

Islamic groups, a role they said the Philippines

Constitution prohibited. Equally significant was the reaction of the

residents of Jolo. A journalist visiting the island shortly after

the announcement reported an outpouring of opposition to the idea of

US troops arriving. A banner in the island’s main port read, “We

will not let history repeat itself! Yankee back off.” The island’s

radio station played traditional ballads with new lyrics: “We heard

the Americans are coming and we are getting ready. We are sharpening

our swords to slaughter them when they come. . . . Our ancestors are

calling for revenge.”25 In the face of growing opposition, the

Philippine Government canceled the exercises on Jolo.26 For the

Moros, whose ballads and storytelling keep events of the past alive,

the US military’s occupation a century before remains a source of

ill will toward the United States.

(Charles Byler, Pacifying the Moros: American Military Government in

the Southern Philippines, 1899-1913 in

http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/milreview/byler.pdf)

When Woodrow Wilson became US

President in 1913, there was a major change in official

American policy concerning the Philippines. While the previous

Republican administrations had predicted the Philippines as a

perpetual American colony, the Wilson administration decided to

start a process that would slowly lead to Philippine independence.

US administration of the Philippines was declared to be temporary

and aimed to develop institutions that would permit and encourage

the eventual establishment of a free and democratic government.

Therefore, US officials concentrated on the creation of such

practical supports for democratic government as public education and

a sound legal system. The Philippines were granted free trade

status, with the US

The question of Philippine independence remained a burning issue

in the politics of both the United States and the islands. The

matter was complicated by the growing economic ties between the two

countries. Although comparatively little American capital was

invested in island industries, US trade bulked larger and larger

until the Philippines became almost entirely dependent upon the

American market. Free trade, established by an act of 1909, was

expanded in 1913.

After 1913, civilians replaced

US Army officers in positions in the provincial government, and

most US soldiers withdrew. Fighting between Moros and government

forces virtually ceased, in part because the disarmament policy had

removed thousands of weapons from the province. Perhaps more

important, the Moros became more supportive of US rule as the

prospects for independence for the Philippines increased; they

realized that independence would probably mean their lands would

fall under the control of the hated Christian Filipinos.

When the US Government promised to grant independence to the

Philippines, the Bangsamoro leaders registered their strong

objection to be part of the Philippine Republic. In the petition to

the US President dated June 9, 1921, the people of the Sulu

archipelago said that they would prefer being part of the US

rather than to be included in an independent Philippine nation (See

Appendix C, Jubair 1999). Bangsamoro leaders meeting in Zamboanga on

February 1, 1924, proposed in their Declaration of Rights and

Purposes that the "Islands of Mindanao and Sulu, and the Island of

Palawan be made an unorganized territory of the United States of

America" in anticipation that in the event the US would decolonize

its colonies and other non-self governing territories the Bangsamoro

homeland would be granted separate independence.

Pershing was replaced as governor of Moro Province by a civilian,

Frank Carpenter.

Though the bloody campaigns against the Moros

officially ended in 1915, US troops continued to encounter

sporadic Moro attacks for the next two decades.

Governor Frank Carpenter asked the Sultan, his heirs, and his

council to sign another agreement with the US on March 22, 1915,

asking the Sultan and his heirs to abdicate their claims to the

throne. Implementation of the 1915 Agreement was further

delayed by negotiations over what the sultan and his heirs would

receive in exchange for their giving up their temporal powers.

In 1916, the Philippine Autonomy Act, popularly known as the

Jones Law, was passed by the US Congress. The law which served as

the new organic act (or constitution) for the Philippines, stated in

its preamble that the eventual independence of the Philippines would

be American policy, subject to the establishment of a stable

government. The law maintained the Governor General of the

Philippines, appointed by the President of the United States, but

established a bicameral Philippine Legislature to replace the

elected Philippine Assembly (lower house) and appointive Philippine

Commission (upper house) previously in place. The Filipino House of

Representatives would be purely elected, while the new Philippine

Senate would have the majority of its members elected by senatorial

district with senators representing non-Christian areas appointed by

the Governor-General. Elections happened on October 3, 1916.

The negotiations which concluded in May 1919 gave the

sultan a life-time payment of P12,000 per annum and allowed him and

his heirs the usufruct use of public lands. Carpenter was confident

that with the settlement final, the sultan would now cooperate with

the US by fully recognizing US sovereignty over Sulu.

When the Republicans regained power in US in

1921, the trend toward bringing Filipinos into the government

was reversed.

Gen. Leonard Wood, former Governor of the Moro province and

responsible of the

Moro

Crater Massacre,

was appointed governor-general. He largely supplanted Filipino

activities with a semimilitary rule. However, the advent of the

Great Depression in the United States in the 1930s and the first

aggressive moves by Japan in Asia (1931) shifted US sentiment

sharply toward the granting of immediate independence to the

Philippines. Members to the elected Philippine legislature lost no

time in lobbying for immediate and complete independence from the

United States. Several independence missions were sent to

Washington, D.C. A civil service was formed and was regularly taken

over by Filipinos, who had effectively gained control by the end of

World War I.

In 1932, the United States Congress passed the

Hare-Hawes Cutting Act, providing for

complete independence of the islands in 1945 after 10 years of

self-government under US supervision. The bill had been drawn up

with the aid of a commission from the Philippines, but

Manuel L.

Quezon, the leader of the leading Nationalist party, opposed it,

partially because of its threat of American tariffs against

Philippine products but principally because of the provisions

leaving naval bases in US hands. Under Quezon's influence, the

Philippine legislature rejected the bill. closely looks like the

Hare-Hawes Cutting Act, but struck the provisions for American bases

and carried a promise of further study to correct “imperfections or

inequalities.”

Manuel Luis Quezon y Molina (b. August 19, 1878 in Baler, Aurora,

Philippines - d. August 1, 1944 in Saranac Lake, New York, United

States) was the first Filipino president of the Commonwealth of the

Philippines under US occupation rule. He is also considered by

most Filipinos, as the second President, after Emilio Aguinaldo,

whose administration did not receive international recognition at

the time. He has the distinction of being the first Senate President

elected to the presidency, the first president elected through a

national election, and was also the first incumbent to secure

re-election (for a partial second term, later extended, due to

amendments to the 1935 Constitution). He is known as the "Father of

the National Language".

In 1934, the United States Congress finally

passed a new Philippine Independence Act, popularly known as the

Tydings-McDuffie Act. The law provided for the granting of

Philippine independence by 1946. It

closely looked like the Hare-Hawes

Cutting Act, but struck the provisions for American bases and

carried a promise of further study to correct “imperfections or

inequalities.”

On March 18, 1935, an assembly of more than 100 Maranao

leaders passed a strong worded manifesto known as the Dansalan

Declaration addressed to the US President vehemently opposed the

annexation of the Bangsamoro homeland in reaction to the US-backed

convention organized to write the Philippine constitution. But the Philippine legislature ratified the Tydings-McDuffie Act

and the new

constitution, approved by President Roosevelt in March 1935, was

accepted by the majority of Philippine people in a plebiscite two months later.

US rule was accompanied by improvements in the education and

health systems of the Philippines; school enrollment rates

multiplied fivefold. By the 1930s, literacy rates had reached 50%.

Several diseases were virtually eliminated. However, the Philippines

remained economically backward. US trade policies encouraged the

export of cash crops and the importation of manufactured goods;

little industrial development occurred. Meanwhile, landlessness

became a serious problem in rural areas; peasants were often reduced

to the status of serfs.

In September

1935 Manuel L. Quezon won the Philippine's first national

presidential election against Emilio Aguinaldo and Bishop

Gregorio Aglipay. Following a plebiscite, the

Commonwealth

of the Philippines was formally established,

featuring a very strong executive, a unicameral National Assembly,

and a Supreme Court composed entirely of Filipinos for the first

time since 1901. The new government embarked on an ambitious agenda

of establishing the basis for national defense, greater control over

the economy, reforms in education, improvement of transport, the

colonization of the island of Mindanao, and the promotion of local

capital and industrialization. The Commonwealth however, was also

faced with agrarian unrest, an uncertain diplomatic and military

situation in South East Asia, and uncertainty about the level of

United States commitment to the future Republic of the Philippines.

To develop defensive forces against possible aggression,

Gen.

Douglas MacArthur was brought to the islands as military adviser

in 1935, and the following year he became field marshal of the

Commonwealth army.

In 1939-40,

the Philippine Constitution was revised to restore a bicameral

Congress, and permit the reelection of President Quezon, who was

eventually

reelected in November 1941.

During the Commonwealth years, Philippines sent one elected Resident

Commissioner to the United States House of Representatives.

WWII and independence

War came unexpectedly to the

Philippines. On December 8, 1941, just ten hours after the

attack on Pearl Harbor, Japan attacked without warning the defending

Philippine and United States troops (about 80,000 troops, four

fifths of them Filipinos) under the command of General Douglas

MacArthur, which surrendered few months later.

President

Quezon and Vice President

Osmeña left for the United States, where they set up a

government in exile.

José P. Laurel

was instructed to remain in Manila because of his prewar, close

relationship with Japanese officials. Laurel was among the

Commonwealth officials instructed by the Japanese Imperial Army to

form a provisional government.

Japanese troops

attacked the islands in many places and launched a pincer drive on

Manila. Aerial bombardment was followed by landings of ground troops

in Luzon. Under the pressure of superior numbers, the defending

forces withdrew to the Bataan Peninsula and to the island of

Corregidor at the entrance to Manila Bay where they entrenched and

tried to hold until the arrival of reinforcements, meanwhile

guarding the entrance to Manila Bay and denying that important

harbor to the Japanese. But no reinforcements were forthcoming.

Manila, declared an open city to stop its destruction, was occupied

by the Japanese on January 2, 1942.

The Philippine defense continued until the final surrender of United

States-Philippine forces on the Bataan Peninsula in April 1942 and

on Corregidor in May.

Many individual

soldiers refused to surrender, however, and guerrilla resistance,

organized and coordinated by US and Philippine army officers,

continued throughout the Japanese occupation. MacArthur was ordered

out by President Roosevelt and left for Australia on March 11, where

he started to plan for a return to the Philippines.

Most of the

80,000 prisoners of war captured by the Japanese at Bataan were

forced to undertake the notorious Bataan Death March to a prison

camp 105 kilometers to the north. It is estimated that as many as

10,000 men died before reaching their destination.

Japanese

occupation of the Philippines was opposed by such a large-scale

underground and guerrilla activity that, by the end of the war,

Japan controlled only twelve of the forty-eight provinces. The major

element of resistance in the Central Luzon area was furnished by the

Hukbalahap (Hukbo ng Bayan Laban sa mga Hapon, "People's Army

Against the Japanese"), which armed some 30,000 people and extended

their control over much of Luzon.

The Japanese military authorities immediately began organizing a new

government structure in the Philippines. They initially organized a

Council of State through which they directed civil affairs until

October 1943, when they declared the Philippines an independent

republic, headed by President José P. Laurel, former Supreme Court

justice.

In August 1944, President Quezon died.

Vice President Sergio Osmeña became president. Osmeña

returned to the Philippines on October 20, 1944, with the

first liberation forces, which surprised the Japanese by landing at

Leyte, in the heart of the islands, after months of US air strikes

against Mindanao.

The landing was

followed (October 23–26) by the greatest naval engagement in

history, called variously the battle of Leyte Gulf and the second

battle of the Philippine Sea. A great US victory, it effectively

destroyed the Japanese navy and opened the way for the recovery of

all the islands. Luzon was invaded (Jan., 1945), and Manila was

taken in February. On July 5, 1945, MacArthur announced “All the

Philippines are now liberated.” Fighting continued until Japan's

formal surrender on September 2, 1945. The Philippines suffered

great loss of life and monstrous physical destruction by the time

the war was over. An estimated 1 million Filipinos had been killed,

and Manila was extensively damaged. The Japanese had suffered over

425,000 dead in the Philippines.

After signing a peace treaty with Japan, the Philippines eventually

received $800m in reparations payments.

Gen. Douglas

MacArthur ordered Laurel arrested for collaborating with the

Japanese. In 1946 he was charged with 132 counts of treason, but was

never brought to trial due to the general amnesty granted by

President Manuel Roxas in 1948.

The Philippine congress met on June 9, 1945, for the first

time since its election in 1941. It faced huge problems. The land

was destroyed by war, the economy destroyed, the country torn by

political warfare and guerrilla violence. Osmeña’s leadership was

challenged in January 1946 when one wing (now the Liberal party) of

the Nationalist party nominated for president

Manuel Roxas, who

defeated Osmeña in April.

As the US was preparing to give the Philippines

commonwealth status in preparation for its independence in 1946,

some Moro leaders favored integration into the republic but majority

from both Sulu and Mindanao protested the plan to incorporate their

homeland into the Philippine state.

In 1946, contrary to its promise under the Bates Treaty "not

to give or sell Sulu or any part of it to any other nation," the

US incorporated Mindanao and Sulu against the will of the Moro

people into the state today known as the Philippine Republic.

But even after their territories were made part of the Republic of

the Philippines in 1946, the Bangsamoro people continued to assert

their right to independence.

The Republic of the Philippines

Manuel Roxas

became the first president of the Republic of the Philippines when

independence was granted, as scheduled, on July 4, 1946.

But his sudden death by heart attack in April 1948 elevated the vice president,

Elpidio Quirino, to the presidency. In November 1949, in a

bitterly contested election Quirino defeated José P. Laurel to win a

four-year term of his own.

In March, 1947,

the Philippines and the United States signed a military assistance

pact and the Philippines gave the United States a 99-year lease on

designated military, naval, and air bases. At the beginning of 1967

a second agreement reduced that period to 25 years

In foreign

affairs, the Philippines maintained a firm anti-Communist policy and

joined the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization in 1954. There were

difficulties with the United States over American military

installations in the islands, and, despite formal recognition in 1956

of full Philippine sovereignty over these bases, tensions increased

until some of the bases were dismantled in 1959.

At the beginning of 1967 a second agreement reduced that period to

25 years.

After independence, efforts to integrate the Muslims into the new

political order met with stiff resistance. It was unlikely that the

Muslim Filipinos, who have had longer cultural history as Muslims

than the Christian Filipinos as Christian, would surrender their

identity.

The enormous

task of reconstructing the war-torn country was complicated by the

activities in central Luzon of the Communist-dominated Hukbalahap

guerrillas (Huks), who resorted to violence in their

efforts to achieve land reform and gain political power.

The Hukbalahap, commonly known as

Huks, was the military arm of the

Communist Party of the Philippines (PKP), formed in 1942 to

fight the

Japanese Empire's occupation of the Philippines during World War

II. The term is a contraction of the Filipino term "Hukbong

Bayan Laban sa mga Hapon", which means "People's Army Against the

Japanese."

They began as several groups of resistance against the Imperial

Japanese Army, mostly joint by agrarian peasants of Central Luzon.

They aimed to lead the Philippines toward

Marxist ideals and

communist revolution.

After its inception

the group grew quickly and by late summer 1943 claimed to have

20,000 active military fighters and 50,000 more in reserve. Weaponry

was obtained primarily by stealing it from battlefields and downed

planes left behind by the Japanese, Filipinos and Americans.

They fought Japanese troops to rid the country of its imperialist

occupation, worked to subvert the Japanese tax-collection service,

intercepted food and supplies to the Japanese troops, and created a

training school where they taught political theory and military

tactics based on Marxist ideas.

In areas that the group controlled, they set up local governments

and instituted land reforms, dividing up the largest estates equally

among the peasants and often killing the landlords.

After the war, the

Hukbalahaps remained active, although to a lesser extent and with

their power diminished.

Under the leadership of

Luis Taruc and Communist Party General Secretary

Jose Lava,

the Hukbalahap

continued waging guerrilla warfare against the United States and

later against the first independent governments. The Hukbalahap Insurrection (1946-1954) was

their attempt to take over the Philippines, but they were accused to

commit rape, robberies and murders against unarmed civilians.

In 1949, Hukbalahap members ambushed and murdered

Aurora Quezon, Chairman of the Philippine Red Cross and widow of

the Philippines' second president,

Manuel L. Quezon, and several others.

Public sympathies for the movement had been waning due to their

postwar attacks, and what remained evaporated following the Quezon

ambush. Without the protection of local supporters, active "Huk"

resistance was eventually defeated in 1954, after a vigorous attack

promoted by President

Ramón Magsaysay. After four months of negotiations led by

Benigno Aquino, Jr.

Taruc surrendered unconditionally to the government.

The Hukbong

Mapagpalya ng Bayan was again ressurected as Bagong Hukbong

Mapagpalaya ng Bayan during the early 1960s, but the Partido

Komunista ng Pilipinas shifted from the use of armed struggle to

parliamentary struggle.

In November 1953, Ramón Magsaysay had became president of the

country, having defeated Quirino. He had promised sweeping economic

changes, and he did make progress in land reform, opening new

settlements outside crowded Luzon island. His death in an airplane

crash in March 1957 was a serious blow to national morale.

Vice President

Carlos P. Garcia succeeded him and won a full term as

president in the elections of November 1957.

In

June 1959, Philippine opposition to García on issues of

government corruption and anti-Americanism led to the union of the

Liberal and Progressive parties, this one led by Vice President

Diosdado

Macapagal.

In the 1961 elections Macapagal succeeded García as

president. Macapagal’s administration was marked by efforts to

combat the mounting inflation that had plagued the republic since

its birth; by attempted alliances with neighboring countries; and by

the Sabah dispute with Britain

and Malaysia.

Malaysia

vigorously opposed the Philippine's territorial claim, arguing that

a certain Baron de Overbeck had "purchased" Sabah from the sultan of

Sulu before later assigning his rights to the British East India

Company. Malaysia further argued that Sabah had become part of

Malaysian territory when Britain granted independence to the

Federated States of Malaysia. The Philippines, by reply, argued a

case of bad semantics, insisting that in 1876 de Overbeck had only

"leased" Sabah from the Sultan of Sulu. The alleged contract between

de Overbeck and the Sultan of Sulu used, they argued, the word

padjak, a Malay term that could mean either "lease" or "purchase."

From the

official website of the ROYAL HASHEMITE SULTANATE OF SULU AND SABAH

http://www.royalsulu.com/issues.htm

The father of HM Sultan Jamalul Kiram II was HM Sultan Jamalul Ahlam

Kiram (Sultan of Sulu and Sabah 1863 to 1881) leased North Borneo/Sabah

to a British Company represented by the two Dent brothers and

Gustavus Baron von Overbeck in 1878. This 1878 North Borneo Lease

states: “The abovementioned territories are from today truly leased

to Gustavus Baron von Overbeck and to Alfred Dent, Esquire, as

already said, together with their heirs, their associates (company)

and to their successors and assigns for as long as they choose or

desire to use them, but the rights and powers hereby leased shall

not be transferred to another nation, or a company of other

nationality, without the consent of His Majesty’s Government.” Based

on facts, reality and history, His Majesty’s Government or the

Government of the Sultan of Sulu as owner never gave its consent to

the 1963 British transfer of Sabah to Malaysia which means that the

“Lease is breached” and based on point of Law, it can be stated that

Sabah must and should be returned to the Lawful Owner namely to the

Sultan of Sulu. Sabah is the private property of the Sultan of Sulu

up to now and the Sabah occupation of Malaysia is unlawful.

THE CONTEMPORARY CONFLICT

The contemporary armed conflict on the Moro front may be set in

periods as follows, based on qualitative changes in the situation,

key issues, decisions, and developments:

1. Formative Years (1968-72)

2. Early Martial Law and Moro War of Liberation (1972-75)

3. First Peace Negotiations and Tripoli Agreement (1975-77)

4. Rest of the Marcos Regime (1977-86)

5. Aquino Administration (1986-92)

6. Ramos Administration (1992-98)

7. Recent Years: Estrada (1998-2001) and Arroyo Administrations

(2001-present)

In the 1960s the central

government in Manila enforced a "homestead" policy, which propelled

the escalation of Christian migration to Mindanao region. Settlers

from Luzon and Visayas occupied part of the Bangsamoro. Local and

foreign big business obtained titles over the lands.

In

the 1965 elections,

Ferdinand E. Marcos succeeded to the

presidency after defeating Macapagal. He inherited the territorial

dispute over Sabah; in 1968 he approved a congressional bill

annexing Sabah to the Philippines. Malaysia suspended diplomatic

relations and

the matter was referred to the United Nations.

Parallel with diplomatic attempts,

Marcos conceived a plot of establishing a force of commandos to

destabilize Sabah, then ultimately to take advantage of the

instability by either intervening in the island on the pretext of

protecting Filipinos living there, or by "the residents themselves

deciding to secede from Malaysia."

The plot brought to the Operation Merdeka, which ended in March 1968

in the

so-called

Jabidah Massacre, in which from 28 to 64 Filipino Muslim

commandos were gunned down by the military in Corregidor, an island

in the entrance of the Philippines' Manila Bay, because they had refused

to invade Sabah.

The Philippines dropped its claim to Sabah only in 1978.

Marcos could not have chosen a more

auspicious time to try and reclaim Sabah. Malaysia was only a

fledgling state at that point, made even more wobbly by the

secession of Singapore in 1965, two years after its independence

from Britain. Too, Malaysia was embroiled in a border dispute with

powerful Indonesia.

The codename for the

destabilization plan was Operation Merdeka. The plan involved the

recruitment of nearly 200 Tausug and Sama Muslims aged 18 to 30 from

Sulu and Tawi-Tawi and their training in the island-town of Simunul

in Tawi-Tawi. The recruits felt giddy about the promise not only of

a monthly allowance, but also over the prospect of eventually

becoming a member of an elite unit in the Philippine Armed Forces.

That meant, among other benefits, guns, which Muslims regard as very