| |

Nepalese Civil War

–

1996/2006

(to present day)

updated at January 2008

|

Source ©

Wikipedia |

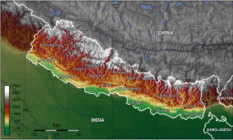

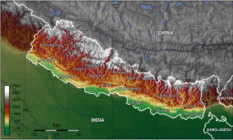

Nepal, officially known according to its Interim Constitution as the

State of Nepal, is a landlocked Himalayan country in South Asia that

overlaps with East Asia, bordered by Tibet to the north and by India

to the south, east and west. For a small territory, the Nepali

landscape is uncommonly diverse, ranging from the humid Terai in the

south to the lofty Himalayas in the north. Nepal boasts eight of the

world's fourteen highest mountains, including Mount Everest on the

border with China. Kathmandu is the capital and largest city

(3 districts) (pop. 2.2 million est.). The

other main cities include Bhaktapur, Patan, Biratnagar, Bhairahawa,

Birgunj, Janakpur, Pokhara, Nepalgunj, and Mahendranagar. The origin

of the name Nepal is uncertain, but the most popular understanding

is that it is derived from the Newari language, which is called the

Nepal language by the Newari people.

Nepali culture is very similar to the cultures of Tibet and India.

There are similarities in clothing, language and food.

Politics

An interim Parliament was formed on January 15, 2007 after a

comprehensive peace agreement between the ruling Seven-Party

Alliance and the Maoist rebels. Prime Minister and Council

of Ministers chosen through political consensus among the

eight ruling parties on April 1, 2007; role of monarchy

suspended, with future status to be decided by upcoming

Constituent Assembly.

Interim constitution

promulgated on January 15, 2007.

(Source: US Department of State)

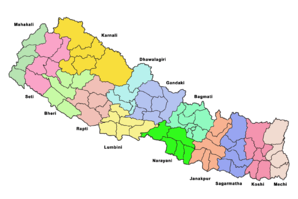

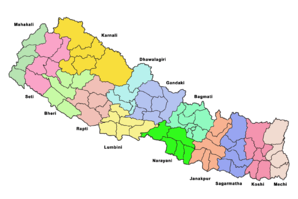

Nepal is

divided into 14

zones and 75

districts, grouped into 5

development regions. Each district is

headed by a fixed chief district officer

responsible for maintaining law and order

and coordinating the work of field agencies

of the various government ministries.

The 14 zones are:

|

TYPE OF CONFLICT

Transition after Maoist insurgency for

state control, the so-called

Nepalese Civil War.

Read on

Mao Zedong and

Maoism

FIGHTING FACTIONS FROM 1996 TO 2006

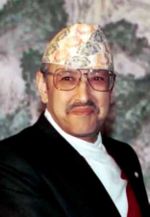

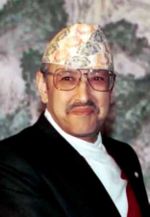

1) Nepali government, led in the last years by

King Gyanendra

and mainly supported

by India and USA.

On April 21, 2006

King Gyanendra gave up his absolute power

in favour of a democratic system.

2) Guerrillas of the Maoist Communist Party of Nepal (CPN or NCP,

Nepalese Communist Party) which is led by Pushpa Kamal Dahal, also

known as

Prachanda (The Fierce), backed by Maoist militia groups

from north-western India.

FIGHTING FACTIONS

AFTER 2006

1) Interim Nepali government.

2) Guerrillas of the

Democratic Terai Liberation Front,

estimated only

150-200 fighters but active from

Saptari to Rautahat districts through its ally the Tarai Tigers.

CASUALTIES

According to IRIN and Reuters, an estimated 12,000 to 13,000

people have died from 1996 to 2006 (over 4,000 killed by Maoists and

8,200 by the government) and an estimated 100,000 to 200,000 people

were internally displaced (Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre).

Read on

internally displaced people

WEAPONS' SUPPLIERS (before 2007)

The government is armed by India, USA and UK. Its troops number

today up to 95,000.

Since 9/11 the Anglo-American coalition has committed millions of

euros in military aid in the name of the "world war against

terrorism". China, Belgium, South Africa, Poland, Russia, Belarus,

Ukraine and France also supply military support to the government.

In 2005, following King Gyanendra’s coup both India and the UK

suspended military aid to Nepal for a brief period of time but later

both countries resumed arms shipments. The US also postponed the

shipment of “lethal arms” to Nepal.

Guerrillas, who emerged in the mid-1990s out of a mix of state

repression and poverty, numbered between about 5000 and 15,000. They

produced their own arms and steal weapons from army barracks. Some

of them were supposed to be trained by other self-declared Maoist

armed groups such as the Naxalists in India and members of Shinning

Path in Peru. It seems they received military assistance also from

Kashmiri separatists and China.

Read on

guerrilla warfare

and

arms industry

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

One of the world's poorest countries, landlocked

Nepal has been under the sway of an hereditary monarchy or ruling

family for most of its known history, largely isolated from the rest

of the world. With its ancient culture and the Himalayas as a

backdrop, Nepal has long been the destination of choice for

travellers in search of adventure.

Neolithic tools found in the Kathmandu Valley indicate that people

have been living in the Himalayan region for at least 9,000 years.

It appears that people who were probably of Tibeto-Burman ethnicity

lived in Nepal 2,500 years ago.

Indo-Aryan tribes entered the valley around 1500 BC. Around 1000 BC,

small kingdoms and confederations of clans arose. One of the princes

of the Shakya confederation was Siddhartha Gautama (563–483

BC), who renounced his royalty to lead an ascetic life and came to

be known as the Buddha ("the one who has awakened"). By 250 BC, the

region came under the influence of the

Mauryan empire of northern

India, and later became a puppet state under the

Gupta Dynasty in

the 4th century. From the late 5th century, rulers called the Licchavis governed the area. The Licchavi dynasty went into decline

in the late 8th century and was followed by a Newar era, from 879,

although the extent of their control over the entire country is

uncertain. By late 11th century, southern Nepal came under the

influence of the

Chalukya Empire of southern India. Under the Chalukyas, Nepal's religious establishment changed as the kings

patronised Hinduism instead of the Buddhism prevailing at that time.

By the early 13th century, leaders were emerging in Nepal whose

names ended with the Sanskrit suffix malla ("wrestler"). Initially

their reign was marked by upheaval, but the kings consolidated their

power over the next 200 years. By late 14th century much of the

country began to come under a unified rule. This unity was

short-lived: in 1482 the kingdom was carved into three – Kathmandu,

Patan, and Bhadgaon – which had petty rivalry for centuries.

In 1765, the Gorkha ruler

Prithvi Narayan Shah set out to unify the

kingdoms, after first seeking arms and aid from Indian kings and

buying the neutrality of bordering Indian kingdoms. After several

bloody battles and sieges, he managed to unify Nepal three years

later. However, the actual war never took place while conquering the

Kathmandu Valley. In fact, it was during the Indra Jaatra, when all

the valley citizens were celebrating the festival, Prithvi Narayan

Shah with his troops captured the valley, virtually without any

effort. This marked the birth of the modern nation of Nepal. A

dispute and subsequent war with

Tibet over control of mountain

passes forced Nepal to retreat and pay heavy repatriations to China,

who came to Tibet's rescue. Rivalry with the

British East India

Company over the annexation of minor states bordering Nepal

eventually led to the brief but bloody

Anglo-Nepalese War (1815–16),

in which Nepal defended its present day borders but lost its

territories west of the Kali River, including present day Uttarakhand state and several Punjab Hill States of present day

Himachal Pradesh. The

Treaty of Sugauli,

signed on December 2, 1815, also ceded parts of the

Terai and

Sikkim to the Company in exchange for Nepalese autonomy.

Factionalism among the royal family led to instability after the

war. In 1846, a discovered plot to overthrow

Jang Bahadur, a

fast-rising military leader by the reigning queen, led to the Kot

Massacre. Armed clashes between military personnel and

administrators loyal to the queen led to the execution of several

hundred princes and chieftains around the country. Bahadur won and

founded the Rana dynasty, leading to the Rana autocracy. The king

was made a titular figure, and the post of Prime Minister was made

powerful and hereditary. The Ranas were staunchly pro-British, and

assisted the British during the

Indian Rebellion of 1857, and later

in both World Wars. In 1923 the United Kingdom, ruled by

King

George V of Windsor,

formally signed with Nepal, ruled by

King Tribhuvan Bir Bikram Shah, an agreement of friendship, in which Nepal's

independence was recognised by the UK.

BACKGROUND TO THE CIVIL WAR

(Read on

civil war,

communism and

democracy)

In the late 1940s, emerging pro-democracy movements and political

parties in Nepal were critical of the Rana autocracy and the

hereditary rule by a small elite at the top of Nepal’s complex

ethnic and caste-based social hierarchy. Meanwhile, Maoist China occupied

Tibet in 1950, making India keen on stability in Nepal, to avoid an

expansive military campaign.

On April 29, 1949, the

Communist Party of Nepal (CPN)

was founded in Calcutta, India. CPN was formed to struggle against the autocratic

Rana regime, feudalism and imperialism. The founding general

secretary was

Pushpa Lal Shrestha.

CPN played an important role in 1951 uprising that overthrew the

Rana regime and India sponsored Tribhuvan as

Nepal's new king. A new government was appointed, mostly comprising

the Nepali Congress Party. After years of power wrangling between

the king and the government, the democratic experiment was dissolved

in 1959, and a "partyless"

Panchayat system was made to govern

Nepal.

In ancient times, a Panchayat was a Nepalese public assembly,

ideally comprised of the five (pancha) most

important caste or occupational groups in the village. A

pancha is a member of a panchayat. From 1962

until the 1990 constitution took effect, assemblies modeled on this

ancient system formed the backbone of political structure in Nepal,

at the village and district levels, and at the top in the National

Panchayat, or Rashtriya Panchayat.

In 1989,

the "Jan Andolan" (People's) pro-democracy Movement was

marked by a unity between the various political parties. Not only

did various Communist parties group together in the

United Left Front, but they also cooperated with parties such as

Nepali Congress. One result of this unity was the formation of

the

Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist-Leninist). Jan Andolan

eliminated the Panchayat system and forced

King Birendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev, ruling

the

absolute monarchy of Nepal since 1972, to accept

large-scale political reforms by creating a

parliamentary monarchy,

with the king as the head of state and a prime minister as the head

of the government. A

multiparty

system was established in Nepali parliament in May

1991.

Expectations of increased

human rights protections, stability and

development came with the new political system. The King, formerly

an absolute monarch, legalized political parties, after which an

interim government promulgated a new

Constitution by which the King

was retaining important residual powers, but dissociated himself

from direct day to day government activities. The democratically

elected Parliament consisted of the House of Representatives (lower

house) and the National Council (upper house).

Despite some improvements, however, there was little progress in

bringing existing legal and administrative provisions fully in line

with international standards and principles enshrined in the

constitution which set up a parliamentary constitutional monarchy.

In 1994, the

Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) was founded

and led by Pushpa Kamal Dahal, otherwise known as

Prachanda.

The CPN-M was formed following a split in the

Communist Party of Nepal (Unity Centre) and it used the name "CPN

(Unity Centre)" until 1995.

On February 13, 1996, the

CPN-M alienated from

mainstream political parties and started a guerrilla war in the

Midwestern region of the country, the “People’s war”, against both

monarchy and mainstream political parties, with the main goal of

overthrowing feudal institutions, including the monarchy, and

establishing a Maoist state.

The rebels were made up of former members of the

1949 Communist Party of Nepal. They were referred to as Maoists

because they claimed an ideological legacy from the Chinese

Revolutionary leader Mao Zedong.

The Maoists' main demand was an end to the monarchy.

They also wanted the expulsion of all Indian influence and an end to

discrimination based on the Hindu caste system, ethnicity and

gender.

Underdevelopment in areas outside the capital, particularly the

mountainous western regions, has fuelled support for the rebels

among the poor, who blame the government for failing to address the

country's gross inequalities.

The districts in which the Maoists hold sway were among the most

inaccessible and impoverished in Nepal. Maoists recruited fighters

in the rural poor and illiterate base and train them in working

camps. But in general, a wide range

of people who face bleak economic prospects, high unemployment rates

and inadequate education and healthcare facilities turned in hope to

the Maoists' cause.

The upsurge in violence hurt Nepal's economy and

deepened political instability.

In 2000, insurgency spread to at least 35

of Nepal’s 75 districts and grave human rights violations

continued, committed both by the Nepalese police force and the CPN-M.

Nepal's stability was threatened even more when King Birendra and

most of his family were massacred at a

royal dinner on 1 June 2001. His eldest son and heir,

Dipendra, was apparently the gunman, in response to his parents'

rejection of his choice of wife. He himself died a few days later of

gunshot wounds suffered during the massacre. Birendra's brother,

Gyanendra

Bir Bikram Shah Dev, then became king.

Following the massacre of the royal family, violence escalated and

the government brought in the army in addition to national police

forces to fight the rebels. On the pretext of quashing the

insurgents, the King Gyanendra closed down the parliament and sacked

the elected prime minister in 2002 and started ruling through prime

ministers appointed by him.

He enhanced military action against guerrillas. CPN-M took under

control about two thirds of the Country. Either government

repression against rebels and those suspected of supporting them,

and Maoist attacks against politicians went on. The new round of

violence prompted the use of the army against the rebels for the

first time. In late July, the newly-elected Prime Minister

Sher

Bahadur Deuba ordered an army

ceasefire and called for dialogue with

the rebels. The rebels agreed to peace talks in August but, by

November, had broken the ceasefire and walked out on the talks.

In 2002 fighting escalated dramatically as government and rebel

forces launched frequent attacks which killed over 4,600 people,

many of them civilians. About 50,000 Royal Nepal Army soldiers -

some equipped with American-made M16s, others with Belgian FNFAL. 762 mm rifles – were opposing the Maoists, numbering between 5,000

and 15,000, widely dispersed in small groups.

Prime Minister Deuba was in turn removed by King Gyanendra, in

October 2002, He dissolved Parliament and called for elections.

In 2003 a

ceasefire between the government and Maoist rebels held for the

first eight months of the year, leading to a decline in

conflict-related deaths. However,

due in part to the continued suspension of the

democratically-elected government, the rebels withdrew from the

ceasefire in August and both sides resumed fighting, resulting in

the death of approximately 1,000 soldiers, rebels and civilians in

less than five months.

The Maoist rebellion had traditionally been

concentrated in the four western districts of Rukum, Rolpa, Salyan

and Jajarkot; however, in 2003 the rebels were active in 72 of

Nepal’s 75 administrative districts.

Heavily criticized for human rights abuses, the Maoists were said to

have imposed an increasingly authoritarian regime on many parts of

rural Nepal, regularly abducting civilians and often forcing at

least one person from each family to join them.

In 2004

mass strikes, riots, kidnappings, blockades, terrorist bombings and

major clashes between Maoist rebels and government security forces

contributed to the conflict, resulting in thousands of deaths.

Thousands more were injured and hundreds of thousands remained

displaced.

A government ambush of Maoists in March involved thousands of

soldiers and resulted in hundreds of deaths. Rebels blockaded the

capital of Kathmandu several times including a major blockade that

almost entirely halted the flow of goods and people in and out of

the city for several days. The King of Nepal controlled the

government while opposition parties and donor agencies pushed for

the restoration of democracy.

Maoist attacks on development and infrastructure projects resulted

in millions of dollars in damages. Several big businesses in Nepal

shut after facing threats from the rebels. Nepali royal family and

American and Indian investors had stakes in some of the businesses

targeted by the rebels, so India was also worried at increasing

rebel attacks on Indian businesses in Nepal.

Nepal Prime Minister Deuba seeked Indian understanding, cooperation

and assistance in tackling the deadly Maoist insurgency, called by

him “terrorism”.

In the past, India had supplied Nepal with helicopters, trucks as

well as arms and ammunition. Deuba also asked India to stop the

Maoists from using Indian territory for shelter, training and

supplies.

RECENT STATUS OF FIGHTING

In 2005,

intense fighting between Maoist rebels and government troops

throughout the year resulted in over 1,500 deaths on both sides.

Human rights violations and the use of child soldiers by the rebels

and the government continued. Thousands of people were arrested in a

year-long crackdown by the government. On February 1, 2005,

the King

unilaterally declared a

state of

emergency, took over all executive powers of the government to

establish an absolute monarchy, being in firm control of the

military. He enforced martial law and argued that civil politicians

were unfit to handle the Maoist insurgency. Telephone lines were cut

and several high-profile political leaders were detained. Other

opposition leaders fled to India and regrouped there. A broad

alliance against the royal takeover called the

Seven Party Alliance

(SPA) was organized, encompassing about 90% of the seats in the old,

dissolved parliament.

At the time, the government security forces consisted of the Armed

Police Force and the Royal Nepalese Army, both having been heavily

criticized for their alleged disregard for human rights. In three

years the Royal Nepalese Army had nearly doubled its strength from

roughly 45,000 troops to 80,000.

Violent local militias armed by

the government were increasingly involved in violent attacks on

suspected rebels and suspected sympathizers, while rebels controlled

much of the countryside. Senior military officers said there were

between 2,000 and 4,000 well-trained Maoist fighters, known as the

movement's ‘hard core’. Another 12,000-14,000 so called ‘militia’

fight alongside them. In July 2006, a Maoist commander was quoted in

local media as saying there were 36,000 fighters.

Though the rebels were active in 72 of Nepal’s 75 administrative

districts, according to diplomats, they did not threaten the

survival of the government, which was always controlling the major

towns and cities.

In September 2005,

fighting decreased following a four-month unilateral ceasefire

declaration by the CPN-M which was not reciprocated by the royal

government.

On November 22, 2005, a joint CPN-M / SPA conference in

Delhi, India, issued a 12-point understanding in

opposition to the monarchy. Within the framework of that

understanding, Maoists committed themselves to multiparty democracy

and freedom of speech. SPA, for their part, accepted the Maoist

demand for elections to a Constituent Assembly. Maoist and SPA

together arranged a mass uprising against the reign of King Gyanendra. Frustrated by lack of security, jobs and good governance,

thousands of people took to the streets to demand that the king

renounce power outright, but the royal government turned even more

ferocious and continued its suppression including daytime curfews

amid a Maoist blockade. Thousands were injured and 21 people died in

the uprising. Food shortages took effect. The security forces turned

brutal while foreign pressure continued to increase on King

Gyanendra to surrender power.

These

political agitations against the rule

of King Gyanendra were called

Loktantra

Andolan (Democracy Movement), also sometimes referred

to as Jana Andolan-II (People's Movement-II), implying it

being a continuation of the 1990 Jana Andolan.

At the beginning of 2006,

the situation became yet more tense as SPA launched agitation

programmes around the country. On January 16, a night curfew was

imposed in the capital, Kathmandu, to avoid demonstrations and

strikes against the king. The police fired at protestors, and

arrested many of them, including leaders of the opposition. The agitations reached a peak

around the February 8 municipal elections, which were boycotted by

the SPA and the Maoists. In total, official figures claimed a

participation of about 21% but opposition sources questioned those

claims.

SPA called for a four-day nationwide general strike between April

5-9, 2006. The Maoists called for a cease-fire in the Kathmandu valley.

The general strike saw numerous protests. A curfew was announced by

the government on April 8, with reported orders to shoot protestors

on sight. Despite this, small, disorganized protests continued.

On April 9, SPA announced that it intended to continue its protests

indefinitely and called for a tax boycott. The government announced

plans to step up its enforcement of the curfew and claimed that the

Maoists had infiltrated the protests. Prachanda, the leader of the

CPN, had said that "this is no longer a protest by opposition

parties ... it has become a people's movement," and warned that he

himself could lead a revolt in the capital.

For four weeks,

large pro-democracy demonstrations,

general strikes and rebel blockades shut down the capital Kathmandu

on multiple occasions.

Clashes between security forces and thousands of

anti-royalists occurred on a daily basis, with crowds increasing to

sizes estimated at 100,000 to 200,000 in Kathmandu in various

estimates, more than 10% of the city population. At least 16 people

were shot dead, dozens were injured, and hundreds were arrested. Any

offers for talks by King Gyanendra were rejected.

On April 21, 2006, a crowd

extimated from 300,000 to about half a million took part in the

protests in Kathmandu.

Later the same evening,

King Gyanendra announced that he was giving up absolute power and

that "Power was being returned to the People". He

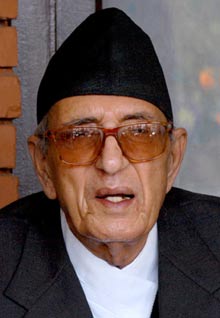

appointed former Prime Minister

Girija Prasad Koirala of the Nepali

Congress Party prime minister once more . Both the U.S. and India

immediately called on the SPA to accept this new situation.

Koirala formed a coalition called the People’s Government and

annulled all appointments made by King Gyanendra since October 2002,

with the intention to hold elections as soon as possible.

Many Nepalese

protesters, however, still carried out rallies in numerous cities.

Maoists stated that merely restoring the parliament was not going to

resolve the problems and that the rebels planned to continue

fighting against government forces until they would achieve the

formation of a Constituent Assembly and the complete abolition of

the monarchy. The SPA felt the pressure of these protests as some

took place directly outside the deliberations of Gyanendra's offer.

Finally after 19 days of tumultuous protests, on April 24 midnight,

the King

reinstated

the old

Nepal House of Representatives

and

called it to reassemble on April

28. Then Maoists

agreed to new Prime Minister Koirala’s appeal to lift city blockades

and few days later a truce offered by the government came into

force. On June 13, the government began releasing rebels detained

under the antiterrorist law introduced in 1998.

The most dramatic move of the new government came on May 18, 2006

when the newly resumed House of Representatives unanimously used its

newly acquired sovereign authority to curtail the power of the king

and declared Nepal a secular state. Parliament stripped the king of

his power over the military, abolished his title as the descendent

of a Hindu God, and required royalty to pay taxes. Furthermore,

several royal officials have been indicted, and the Nepalese

government is no longer referred to as "His Majesty's Government",

but rather as the "Government of Nepal". An election of the

constituent assembly to rewrite the constitution was declared

unanimously to be held in the near future, with the possible

abolition of the monarchy as part of constitutional change.

The bill included:

Putting 90,000 troops in the hands of the parliament

Placing a tax on the royal family and its assets

Ending the Raj Parishad, a royal advisory council

Eliminating royal references from army and government titles

Declaring Nepal a secular country, not a Hindu Kingdom

Scrapping the king's position as

the supreme commander of the Army

The act overrides the 1990 Constitution, written up following the

Jana Andolan and has been described as a Nepalese Magna Carta.

According to Prime Minister Koirala, "This proclamation represents

the feelings of all the people."

May 18 has already been named Loktantrik Day (Democracy Day) by

some.

Following Gyanendra's relinquishing of absolute power, the Nepalese

government and CPN-M rebels agreed on a ceasefire.

In August 2006,

both parties came to an agreement on the issue of arms

accountability: the rebels and their arms were to be confined to

camps while government troops would be stationed in their barracks.

The U.N. was requested to monitor both.

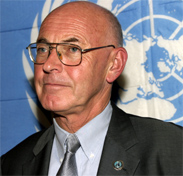

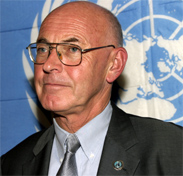

The UN Secretary-General decided

to appoint Ian

Martin ( United Kingdom) as his Personal Representative in Nepal

for support to the peace process.

A lasting peace finally seemed within reach in early November when

the two sides resolved the thorny issue of what the rebels would do

with their weapons.

Under the pact, the Maoists agreed to put their arms under U.N.

supervision, clearing a key hurdle for the guerrillas to join the

interim government.

On November 21, 2006, peace talks ended with the signing of

the Comprehensive Peace Accord (CPA) between Prime Minister

Koirala and Maoist leader Prachanda.

This formally ended the Nepalese Civil War, which claimed more than

13,000 lives and displaced hundreds of thousands of people to avoid

violence and abuse. At least 900 people disappeared after they were

detained by the security forces while the CPN-M is responsible for

several hundreds of killings, abductions and torture of people seen

as opposed to their cause.

On January 14, 2007, SPA and CPN-M served together in an

interim legislature under the new Interim Constitution of Nepal

awaiting elections in June 2007 to a Constituent Assembly, while all

the powers of the Nepali King were in

abeyance.

The new 330-seat

parliament was sworn-in.

The Maoists made up the second-biggest party in the new body with 83

seats.

The deal was widely viewed as a victory for peace and democracy in

one of the world's poorest countries. Analysts said their entry into

their parliamentary system signalled their commitment to abandon

their insurgency and participate in democratic politics.

Following

the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, the

United Nations received a

request for assistance,

and established the political mission United Nations Mission in

Nepal (UNMIN) on 23

January 2007, to monitor the disarmament of Maoist rebels and sent

an

advance group of up to 35 military monitors and a team of up to 25

election experts to help with the 2007 poll for

Constituent Assembly elections in 2007.

Later the UNMIN included a team

of 186 military monitors.

STATUS OF FIGHTING AT PRESENT

DAY

An outbreak of violence in January 2007 cast a shadow over the peace process, as the

Madhesi

(or Madhesay)

movement in the

southern plains region called

Terai demanded to end discrimination against

the ethnic Madhesi people.

Violent protests

erupted at which Madhesi

protestors called for greater representation in government and the

peace process. Clashes between police and demonstrators

and attacks on government facilities in at least 10 districts

resulted in the death of over 30 people and some towns were put under curfew.

A Nepali

minister from the ethnic Madhesi community resigned, accusing the

ruling alliance of neglecting Madhesi grievances. Madhesi leaders

were angry after parliament passed the Interim Constitution that did

not meet their demands for federalism and proportional

representation.

They warned that, if the unrest continued, the military might

intervene and wider communal conflict could break out, threatening

the peace process. Aid agencies said the clashes and curfews were

stopping people accessing health services, and called on those

involved to allow humanitarian workers to operate freely.

Jwala Singh (real name Nagendra Paswan), leader of

the breakaway

Democratic Terai Liberation Front

(in Nepali language Janatantrik Terai Mukti

Morcha or JTMM), said he was ready

for talks with the government. He also demanded

the Madhesi to be allowed to run themselves the army,

police and the local administration

of Nepal's fertile southern plains bordering India.

Prime Minister Koirala, in an address to the nation on February

7, 2007, promised to amend the constitution to meet the demands

of the Terai people.

The Madhesi, roughly a third of Nepal's population, are ethnically and culturally closer to people from

neighbouring Indian states than Nepalis from the hills and say they

are discriminated against in parliament and the security forces,

having always been largely excluded from political power and

representation.

They live in a fertile border strip, and are the ethnic majority in

the area, which is home to almost half the country's population of

26 million.

Read a History of Terai in on

Madhesi Wordpress, from a Madhesi point of view.

Janatantrik Terai Mukti Morcha

was a revolutionary organisation in Nepal. It was formed in 2004 by

former Maoist Leader

Jay Krishna Goit as a split

from the CPN-M. The group accused the CPN-M of not guaranteeing the

autonomy of the Terai region. In August 2005, several of its leading

members were killed in fight with the CPN-M. In July 2006, it was

accused of killing two CPN-M members in a gunfight . The CPN-M

followed this incident by declaring an armed war with the group,

claiming that they had ignored calls for peace talks and that there

were royalist elements in the JTMM.

Clashes among pro-royalists, Maoist former rebels, Madhesi People's

Rights Forum for regional autonomy and other parties broke out in

the first part of 2007, showing how long was the way for

democracy to take root in Nepal. Scores of people died in the region

in violence by ethnic Madhesi groups indicating that an agreement

between the government and the main Madhesi group would not end the

unrest in the region unless other rebel groups were also brought

into the mainstream.

Mr Ian Martin, U.N. Secretary-General's representative to the Nepal's peace

process, warned that the violence could also delay elections due to

be held in June 2007 for a special assembly tasked with drafting a

new constitution and deciding on the monarchy's future.

U.N. human rights monitors also hoped to promote a criminal justice

system that would be accessible to all, including lower castes,

women, survivors of sexual violence and the rural poor. But little

progress has been made on how to deal with crimes perpetrated during

the conflict.

Another key unanswered question is the role - if any - of the

monarchy in the future political landscape. The Maoists have

softened their demand for its abolition, saying they will accept the

decision of the Nepalese people. Washington and other Western

governments backed away from their previous support for the king

after he became increasingly autocratic, indicating that he should

play little more than a ceremonial role.

The return to multi-party democracy may not produce a stable

government.

On April 1, 2007, a new

eight-party government was sworn in, with five ministers from CPN-M.

The Maoists were placed in charge of the ministries of information,

local development, planning and works, forestry, and women and

children. But on September 18, 2007, the CPN-M ministers

resigned from the government due to the rejection of its demands,

which included the declaration of a republic prior to the

Constituent Assembly election planned for November and an electoral

system of proportional representation.

On September 30, 2007,

three

near-simultaneous bomb blasts killed two women and wounded 26 people

in Kathmandu. It was the first attack in the Nepali capital since

the end of the Maoist revolt. The Terai Army,

one of several ethnic Madhesi rebel groups, as well as the

previously unheard of Terai Utthan Sangat, claimed responsibility

for the attacks in calls to local media. The claims could not be

verified independently.

On November 20, 2007, figures compiled by the NGO

HimRights

show that a total of 82 persons were killed by rebel groups, Maoists

and state forces in the 10 districts of the eastern and central

Terai over a five-month period. Amnesty International

expressed concern over the indefinite postponement of the elections

to a Constituent Assembly (CA) which will write a new constitution

and confirm the country as a republic after centuries of royal rule.

As a result of the international pressure, Nepal's government set 10

April 2008 as the date for the elections.

In the meanwhile, human Rights

violations, killing, abduction, kidnap for ransom and vandalizing

activities were observed throughout the country, but especially in

the eastern part of Terai, making the whole region unstable. Some of

the armed groups to function in the region were JTTM (G), JTTM (JS),

Madhesi Tiger, Terai Army and various other unidentified groups.

Even though the functioning armed groups were claiming their

activity for liberation and rights of the Madhesis, the nature of

their work was considered criminal.

Even cadres of Maoists (YCL) continued their acts of abduction,

torture and vandalisation.

In February 2008 at least

two people were killed and hundreds injured in clashes with police

during a strike that closed roads, factories, schools and shops in

the Terai and hindered supplies of fuel travelling from India to the

hills. As the strike didn't stop, Nepal's government agreed to

give autonomy to its southern plains and other regions after the

forthcoming national election.

HUMAN RIGHTS

Human rights violations by both the government security forces and

CPN-M members have been reported during the conflict on a daily basis in 27 of 75

districts. The Maoist insurrection has been waged through torture,

killings, and bombings involving civilians and public officials.

The rebels used guerrilla tactics such as ambushes and bombing.

According to the Ban Landmine Campaign Nepal, both the army and the

Maoists have been using landmines, which have victimised civilians

more than the combatants.

Both the rebels and security forces targeted civilians; the rebels

attacking those deemed “enemies of the people”, including

politicians and teachers, and government forces targeting those

perceived to be supportive of the Maoist cause.

A government initiative to create

civil defence groups to fight the Maoists threatened to further draw

the civilian population into the conflict.

Aside from civilian casualties, the conflict also

produced a significant number of both internally and externally

displaced persons.

During the second half of 2003,

media reported some 200,000 displaced in urban areas across the

country with 100,000 IDPs (Internally Displaced People) in Kathmandu

alone.

If one includes those who have fled to India, the

total number of people displaced, directly or indirectly, by the

conflict could grow to as many as two million people.

IDPs include former land-owners, political party members and

families who have left their villages in search of work after the

war destroyed their livelihoods.

According to the United Nations,

some highland villages have lost up to 80 percent of their

population with only vulnerable groups, such as the elderly, left

behind.

Nepal is also home to refugees from other countries. The U.N.

refugee body, UNHCR, says about 105,000 Nepali-speaking Bhutanese

refugees live in camps in Nepal, having been stripped of their

nationality and expelled from Bhutan in the early 1990s.

There are also about 20,000 Tibetan refugees.

Both the CPN-M and the Royal Nepalese Army have involved

children as young as 14, including girls.

CWIN (Child Workers in Nepal Concerned Centre) estimated that 405

children under 18, including 115 girls, have been killed in the

conflict so far.

UNICEF has also received reports

of Maoists using children as cooks and porters near the frontline.

On a trip to the Maoist heartland in 2005, a Reuters team saw

children scarcely older than 10 lugging rifles, members of a Maoist

militia.

According to UNICEF, thousands of children remain

missing.

The conflict has severely disrupted the education system, UNICEF

said. Maoists have killed and threatened

teachers, and kidnapped thousands of school-children.

The fighting has also hampered the government's ability to deliver

even basic healthcare. Half of all children under the age of five

are underweight, according to the U.N. Development Programme.

NEPAL'S CONSTITUTIONAL PROCESS

Nepal’s constitution-making process must conclusively end

the conflict and also shape more representative and responsive state

structures.

But

political leaders must make the constitutional

process more inclusive or risk a return to violent conflict.

The major challenge is to maintain leadership-level consensus while

building a broad-based and inclusive process that limits room for

spoilers and ensures long-term popular legitimacy. So far, the

concentration has been on building elite consensus at the expense of

intense political debate and extensive public consultation.

Recent violent protests show that providing constructive means to

channel popular demands into political debate is not an abstract

consideration but an urgent practical imperative.

The new constitution’s drafting process must address the twin

objectives of peace-building and long-term political reform. The

interim constitution of 15 January 2007 established a framework for

constitutional change – through an elected constituent assembly –

and enshrined the guiding principles agreed in earlier negotiations.

Mainstream political parties will remain key actors, especially if

they seize this opportunity to increase their inclusiveness, promote

internal democracy and tackle the worst excesses of corruption and

patronage. The Maoists were a driving force for a constituent

assembly, but they now have to translate the achievement of this

goal into votes and prove that their movement can adapt itself to

democratic rules. Other political parties, civil society and the

international community should maintain pressure on them to keep

their promise to abandon violence.

Even a successful constitutional assembly, which should be elected

at the end of 2007, cannot in itself resolve

the social and political conflicts that fuelled the Maoist CPN

insurgency. In facts, although the 10-year civil conflict has ended,

there are widespread law and order problems, many of them political.

However, the constitution-making process is an opportunity both to

reshape the state and encourage reform of the political parties that

will have to consolidate democracy and prevent a return to violent

conflict.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE COUNTRY

In May 2006, Dutch development agency SNV and French

NGO Action Contre la Faim warned of a growing food crisis in remote

districts of impoverished Karnali province in the northwest, caused

by a severe drought.

Development experts told a December 2005 workshop hosted by the

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Nepal Press

Institute that, while Nepal was on track to half the number of

people living below the poverty line from 42 percent in 1990 to 21

percent in 2015, its progress was fragile.

According to the United Nations, the conflict cut the growth rate to

2 percent in 2004-05, but the return to peace - if it lasts - could

help boost tourism and wider economic growth.

Tackling growing inequalities between social groups is seen as a key

challenge for the development community in Nepal. Dr Yubaraj

Khatiwada, Executive Director of the Nepal Rasta Bank, told the UNDP

seminar: "Unless we look at inequality, social conflict may remain

forever, even though the armed conflict may end."

With regard to the Millennium Development Goals, the United Nations

has said Nepal is likely to meet targets for cutting infant death

rates and increasing access to safe drinking water, but could miss

targets on education and stemming the spread of HIV/AIDS.

In May 2007, a senior finance ministry official said the country would

need around $1.2 billion for post-conflict reconstruction, and

appealed to the international community for help. According to

figures from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development, Nepal received $427 million in overseas aid in 2004 -

60 percent of which was earmarked for education, health and other

social sectors.

Population pressure on natural resources is increasing.

Overpopulation is already straining the "carrying capacity" of the

middle hill areas, particularly the Kathmandu Valley, resulting in

the depletion of forest cover for crops, fuel and fodder, and

contributing to erosion and flooding. Additionally, water supplies

within the Kathmandu Valley are not considered safe for consumption,

and disease outbreaks are not uncommon. Progress has been achieved

in education, health, and infrastructure. A countrywide primary

education system is under development, and Tribhuvan University has

several campuses. Although eradication efforts continue, malaria has

been controlled in the fertile but previously uninhabitable Terai

region in the south. Kathmandu is linked to India and nearby hill

regions by an expanding highway network.

On January 2008,

the state-owned Nepal Oil Corporation (NOC), which has a monopoly

over oil imports, had increased kerosene, cooking gas and diesel

prices by up to 20 percent. It was the second price rise since

October. Nepal buys about 800,000 tonnes of oil annually, accounting

for about 10 percent of its energy needs, but it faced shortages

because of lack of money to pay for imports. NOC needed to raise the

prices to cut its losses and attempt to minimise fuel shortages, but

even to help pay bills worth millions of dollars to India's

state-run Indian Oil Corporation (IOC), the sole supplier of oil to

Nepal.

The move was greeted with nationwide protests from student activists

which caused two days of disruption across the country. In Kathmandu,

protesters had blocked many roads and blackened the sky by burning

logs and tyres, till NOC withdraw the increase.

LOCAL e-news

Kantipur

SOURCES

Alertnet

Amnesty International

BBCnews

CIA The World Factbook

HIIK - Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research

HimRights - Himalayan Human Rights Monitors

ICG - International Crisis Group

IRIN - Integrated Regional Information Networks

PeaceReporter

Project Ploughshares

Reuters

UNDP - United Nations Development Programme

US Department of State

Warnews

Wikipedia

up

|

Nepal has a total population of

28,901,790 as of

July 2007, with a

growth rate of 2.13%.

Ethnic groups

2001 census:

Chhettri 15.5%

Brahman-Hill 12.5%

Magar 7%

Tharu 6.6%

Tamang 5.5%

Newar 5.4%

Kami 3.9%

Yadav 3.9%

other 32.7%

unspecified 2.8%

Nepali is the

official language with 47.8% of the population speaking it as their first

language.

Religions

2001 census: Hindus 80.6%

Buddhists 10.7%

Muslims 4.2

Kirant 3.6

other religions 0.9%.

Life expectancy

is 60.56 years. 62% of the population is up to 14 years old,

being the median age less than 21.

Nepal is the only country in the world

where males outlive females.

Total

literacy rate

(2001 census) is 48.6% (62.7% for males and

34.9% for females).

Demographic data from 2007 CIA World Factbook

Economy: Nepal is among the poorest and least developed

countries in the world with almost one-third of its population

living below the poverty line.

(CIA)

GDP (PPP)(2006 est.)(CIA)

- Total $41.18 billion

-

Per capita

$1,500

- Grow rate

1.9%

Gini coefficient 37.7-47.2 (high)(CIA 2004/05-UN 2003/04)

HDI

0.527 (138th) (UNDP 2006)

Poverty

68.5% of the population live on less than $2 per day

(UNDP 2006)

30.9% of the population live below national poverty line (UNDP 2006)

Unemploy-ment rate

42% (2004 est.)(CIA)

Child labour

31% (5-14 year olds) (1999-2004) (UNICEF)

Under-five mortality rate

76‰ (UNDP 2006)

Military ex-penditures

1.6% of GDP (2006)(CIA)

Nepal's military consists of the nearly 95,000-strong Nepalese Army

(NA), which is organized into six divisions (Far-Western,

Mid-Western, Western, Central, Eastern, and Valley Divisions) with

separate Aviation, Parachute, and Security Brigades as well as

brigade-sized directorates encompa-ssing air defense, artillery,

engineers, logistics, and signals which provide general support to

the NA. The Prime Minister is the Supreme Commander of the NA.

(US Dep of State)

Sources

CIA Factbook

UNICEF

UNDP

US Dep State

|